Institutional trends 2022|

|

|

Mainland China

In the 2000s, an IP rights holder would receive expected damage compensation from infringement litigation for possibly not more than USD20,000 on average. A variety of reasons led to this situation, including insufficient ways to collect evidence, limited experience in handling IP infringement actions, and the depth and breadth of IP rights.

As time has passed, the situation has changed and, recently, it reached a critical point as a batch of typical IP cases were issued by the Supreme People’s Court (SPC), and RMB159 million (USD24.6 million) in damages were awarded to the owner of a trade secret for manufacturing vanillin, the most widely used spice in food industries – the highest damages affirmed by the SPC to date.

The record is likely to be broken again soon because such an amount was just a part of damages until the end of 2017. The rights holder may apply for additional damages for the infringements that occurred after 2017, as the Unfair Competition Law introduced punitive damages in 2018.

Assistant Director of Litigation Department at CCPIT Patent and Trademark Law Office in Beijing

Tel: +86 10 6604 6247

Email: jinx@ccpit-patent.com.cn

Larger damages have become more common in IP infringement actions. On the one hand, more Chinese companies have realised the importance of IP when running their business. More than 1.497 million invention patent applications were filed in 2020, plus 2.927 million utility model applications and 770,000 design patents. Meanwhile, 5.761 million trademarks were registered in 2020. These IP rights provide more available options for the rights holder when enforcement is needed.

On the other hand, the Chinese courts now are exploring new ways to strengthen the protection of IP rights and to ascertain the damages. In addition to the introduction of the court’s technical expert to assist the judge, court orders and evidence preservation have become increasingly popular in practice. In many cases, it can be seen that the objective behind petitioning the court to take or preserve evidence is not merely to obtain the defendant’s financial data, but is more like a litigation strategy used to seek large damages.

In practice, few defendants choose to submit financial data like sales records or the profit margin of the accused infringing product, even when facing a court order requiring them to do so. This would lead to rather favourable consequences for plaintiffs. For example, when a defendant refuses to provide financial data without good cause, the court may presume that the plaintiff’s claim for damages is tenable.

As evidence preservation becomes more common and popular in IP litigation, the court has a better chance of finding out the damages caused by the infringement, resulting in an increasing amount of compensation in such litigation.

Some recent cases published by the SPC reveal that the owners of IP rights use combined strategies when proving the damages in a trial. In the vanillin case, the plaintiff tried various ways to show the damages, including the damages suffered by the plaintiff, the profits obtained through infringement, and the change of the market shares caused by the infringement.

The combined strategies brought significant advantages to the plaintiff because the damages calculated through different routes can be cross-referenced so that the judge may feel more comfortable with the amount of compensation finally decided in the sentence. This may become critical in securing larger damages in IP infringement litigation.

In the vanillin case, the plaintiff first began with the loss suffered by the infringement. This is relatively easy when calculating, but difficult in convincing the judge because the loss may have been caused by various reasons, like the change of seasons, advertisements and/or raw material prices.

However, the loss suffered could be a good starting point to give the judge a general picture of how huge the loss could be. Another reason to begin with the loss suffered by the infringement is that the data relating to the loss typically can be collected and calculated by the plaintiff. In this case, the measure of damages derived from this route was about RMB116 million.

Evidence then focused on the profits gained by the accused infringer, which was accepted by the SPC and resulted in the final damages. Here, the plaintiff proved that the production capability of the defendant was at least about 5,000 tons per year, and had tripled since 2015. Based on that, the defendant had to allege that the annual production of vanillin was about 2,000 tons per year, which became the basis of damages to be calculated in this case.

The court confirmed this number because it was rather conservative compared to the total production capability of 17,000 tons per year. The measure of damages was about RMB155 million based on the capability of 2,000 tons per year plus RMB3.4 million in reasonable expenses for stopping the infringement through trial.

The final route adopted by the plaintiff is the change of market share. The plaintiff found out that the market share had dramatically shrunk since the trade secret had been infringed. The damages calculated through the change of the market share were up to RMB790 million. Although the court did not accept the damages amount based on the drop of market share, the author believes the highest damage demand through this route did open good room for the final damages decided by the court.

In the trial, the plaintiff requested a court order asking the defendant to disclose the profit margin, and the refusal of the defendant was taken into the court’s account when deciding the damages. The court held that the defendant’s refusal to disclose the profit margin led to great difficulty in ascertaining the exact profits gained by infringement, and stopped the court from finding out the actual profit margin of the defendant. However, the court used the plaintiff’s profit margin in the calculation, leading to RMB159 million in damages.

This is a remarkable change because in the past the courts tended to reject the plaintiff’s calculation if the plaintiff could not provide the defendant’s financial data because of insufficient evidence, no matter how difficult it was for the plaintiff to access that evidence.

The trial courts rejected the plaintiff’s claims for the same reason, but only awarded statutory damages of RMB3 million. The appellate court, the SPC, reversed and shifted the burden of proof to the defendant in the appeal, resulting in the highest damages in trade secret infringement litigation to date.

Given the SPC case, it is foreseeable that the Chinese courts will more often consider the shifting of the burden of proof during IP infringement litigation if the financial data of the defendant is not accessible to the plaintiff.

The result is, as the vanillin case shows, the measure of damages will keep increasing because the biggest obstacle for patentees to obtain high compensation seems to be gradually disappearing.

CCPIT PATENT AND TRADEMARK LAW OFFICE

10/F, Ocean Plaza,158 Fuxingmennei Street, Beijing 100031, China

Tel: +86 10 66412 3465

Email: mail@ccpit-patent.com.cn

India

India has been attracting global attention with its evolving IP ecosystem. Like any other jurisdiction, certain provisions in India’s patent law are unique, and this article aims to briefly explain these while providing some patent-related updates from India.

The foreign filing licence

One such unique provision relates to the requirement of the foreign filing licence (FFL). There are two options for complying with this requirement. The first is that before filing the first application outside India, the Indian resident inventor applies to the Indian Patent Office (IPO) for issuance of an

Managing partner at LexOrbis in New Delhi

Tel: +91 98111 61518

Email: manisha@lexorbis.com

FFL by submitting a brief disclosure of the invention. Within three weeks of such a request, the IPO issues the FFL to the Indian resident inventor provided the disclosure does not pertain to defence technology or atomic energy. After obtaining the FFL, the first patent application for the same invention can be filed outside India with the name of the Indian resident inventor.

The second option is that, instead of obtaining the FFL from the IPO, the applicant files the first application in India, naming the resident inventor. If there is no objection from the IPO within six weeks, the applicant can file subsequent applications outside India. If the IPO has any objection to the filing of subsequent applications outside India, it may issue secrecy directions to that effect to the applicant. This power has rarely been exercised by the IPO. If no objection is received, the applicant is free to file a subsequent application after six weeks.

Phase filing and amendments

The IPO accepts the English language, which means no translation in native languages is required for filing and prosecuting patent applications in India. This leads to a significant reduction in the overall cost of patenting compared to jurisdictions like Japan, China, Brazil and South Korea, which all require native-language translations.

According to one estimate, translation into the native language generally costs about 35% of the total cost of patent protection. Indian patent law also allows a 31-month period to file a national phase application, based on the international patent co-operation treaty (PCT) against the 30 months provided by most jurisdictions.

The prosecution process

The patent prosecution process in India begins with the request for examination, which brings the application in the queue. Most of the backlog has been cleared, and now applications are getting examined within a year from the date of request. The applicant gets six months to respond to the first examination report. If all objections are successfully overcome, a patent is directly granted. Otherwise, an oral hearing takes place after some time to allow the applicant to address outstanding objections and, thereafter, a decision is issued. In case of an unfavourable decision, the applicant has two remedies – the first is to file a review petition before the patent office and the second is to file an appeal before an appropriate high court.

Divisional applications

A divisional application can be filed any time before the grant or refusal of its parent application. Since there is no advance notice of decision on a patent application, the divisional application should be filed at the earliest opportunity. The divisional application is considered valid only when there are multiple inventions disclosed in the parent application, and the claims of the divisional application are distinct from the claims of the parent application.

Specifically, the independent claims of divisional applications should have at least one inventive feature that was not claimed in the parent application. The claims should also be supported in the description of the parent application. The divisional application can be filed either voluntarily, or in

Partner at LexOrbis in New Delhi

Tel: + 91 97 1126 2818

Email: joginder@lexorbis.com

response to a lack of unity objection from the IPO. The current position on the maintainability of voluntary divisional applications in India is a bit complex. The same has emerged from recent case laws, such as: Procter & Gamble Company v the Controller of Patents & Designs; Esco Corporation v the Controller of Patents & Designs; and UCB Pharma v the Controller of Patents.

In the above-mentioned cases, the Intellectual Property Appellate Board (IPAB) has held, among other things, that the claims of the divisional application are required to be derived from the claims of the parent application only. This is a very restrictive interpretation of laws relating to a divisional application. However, since this position is coming from the multiple decisions of the board, and has not been stayed or challenged, the IPO is likely to object to a divisional application that includes claims absent in the parent application. This can be circumvented by introducing the claims meant for divisional in the parent application itself.

If those claims get accepted in the parent application, that should be good enough for the applicant. Otherwise, the parent application will receive an objection for lack of unity, or newly added subject matter and, as in Milliken & Company v Union of India, such an objection provides a legitimate ground for the applicant to pursue the objected claims through a divisional application.

Disclosure of foreign applications

This legal requirement under the Indian Patent law continues to be a pain point for many applicants, particularly for big filers in various countries. The requirement is divided into two parts. The first part is known as the section 8(1) requirement, under which the IPO is required to be informed about the details of all related or corresponding applications filed anywhere outside India. The related or corresponding application includes any application originating from a common priority or PCT application, the national phase, continuation, continuation in part, and/or divisional application.

All necessary information about the corresponding applications is required to be filed on form 3 at the time of, or within six months from, the date of filing of the Indian patent application. After that, if any new corresponding application is filed anywhere outside India, the details of that application are required to be provided to the IPO on form 3 within six months from the filing.

The second part of the section 8 requirement, under section 8(2), relates to providing copies of the search or examination reports and granted claims in corresponding applications to the IPO, as and when it demands. Such demands are usually made by the controllers in the first examination report. However, since the IPO has now joined as a provider and accessing office to the World Intellectual Property Organisation Centralised Access to Search and Examination (WIPO CASE) system, the controllers now have the facility to access the search and examination reports of the corresponding application through the WIPO CASE system and, therefore, the demand made for such documents by the controller is continually decreasing.

Working statement

Another unique provision in the Indian Patent Law is the requirement of a working statement. Recently, the government introduced a few changes in the format and procedures involved in filing working statements for patents. The changes became effective from 19 October 2020, and the new format and procedure would apply to the working statement to be filed in 2021 onwards. The filing date for the annual working statement has been changed from 31 March to 31 September each year. The period of working to be covered under the new working statement has been replaced from calendar year January to December, to financial year April to March. No working statement is required to be filed in the financial year in which the patent is granted.

A single working statement in form 27 can be filed in respect of multiple related patents, where the approximate revenue or value accrued from a particular patented invention cannot be derived separately from the approximate revenue or value accrued from related patents, and all such patents are granted to the same patentee.

Co-owners of a patent can jointly file one working statement for one or related patents, however, each licensee would be required to file the statements separately. The requirement for providing the quantum of patented products manufactured and/or imported into India has been done away with. There is no requirement for providing the details of licences issued in any given financial year in the working statement.

Abolishment of IPAB

The government has recently abolished the IPAB, the appellate authority for appeals related to IP rights matters. New appeals related to the Patents Act, Trademarks Act and Geographical Indications Act are now to be filed before the relevant high court. The recent parliamentary standing committee report on a review of IP rights regime in India suggests re-institution of the IPAB.

Delhi High Court has, on 7 July, announced the creation of an IP division within the high court for handling all IP rights matters, including those to be transferred from the IPAB. Delhi High Court, however, is yet to notify the rules of the IP division. Other high courts may also follow the initiative of Delhi High Court and start IP divisions soon.

LEXORBIS

709/710 Tolstoy House 15-17

Tolstoy Marg New Delhi

110 001, India

Tel: +91 11 2371 6565

Email: mail@lexorbis.com

Japan

Under economic challenges brought by the pandemic, an accurate understanding of the values and risks of patents, and efficiently utilising them, are more important to protect business and profits. The patent situation in Japan has changed rapidly in the past few years, and it may have a significant impact on business.

Japanese patent rights have become significantly more powerful in the past few years, with obtaining patents and filing patent infringement lawsuits becoming a more attractive option. At the same time, the risks of patent infringement are significantly bigger, and a careful evaluation is highly important when conducting business. This article explains this situation with objective data, which indicates this “pro-patent” tendency.

Recent situation

Attorney at Law at Ohno & Partners in Tokyo

Tel: +813 5218 2339

Email: tadah@oslaw.org

Japan has recently given much stronger protection over patent rights. For example, the country has amended damages presumption clauses of the Japanese Patent Act to make it easier for a patent owner to prove more serious damages, as mentioned in article 102 of the act. Also, article 105-2 stipulates a newly established inspection system to make it easier for a patent owner to collect evidence under the control of an accused infringer. As a patent litigator, the author feels that judges are more friendly towards a patent owner than before.

Winning rates of patent owners

The winning rates of patent owners has rapidly increased in the past few years. The Intellectual Property High Court since 2014 has annually disclosed statistics regarding patent infringement lawsuits.

Expansion of infringement

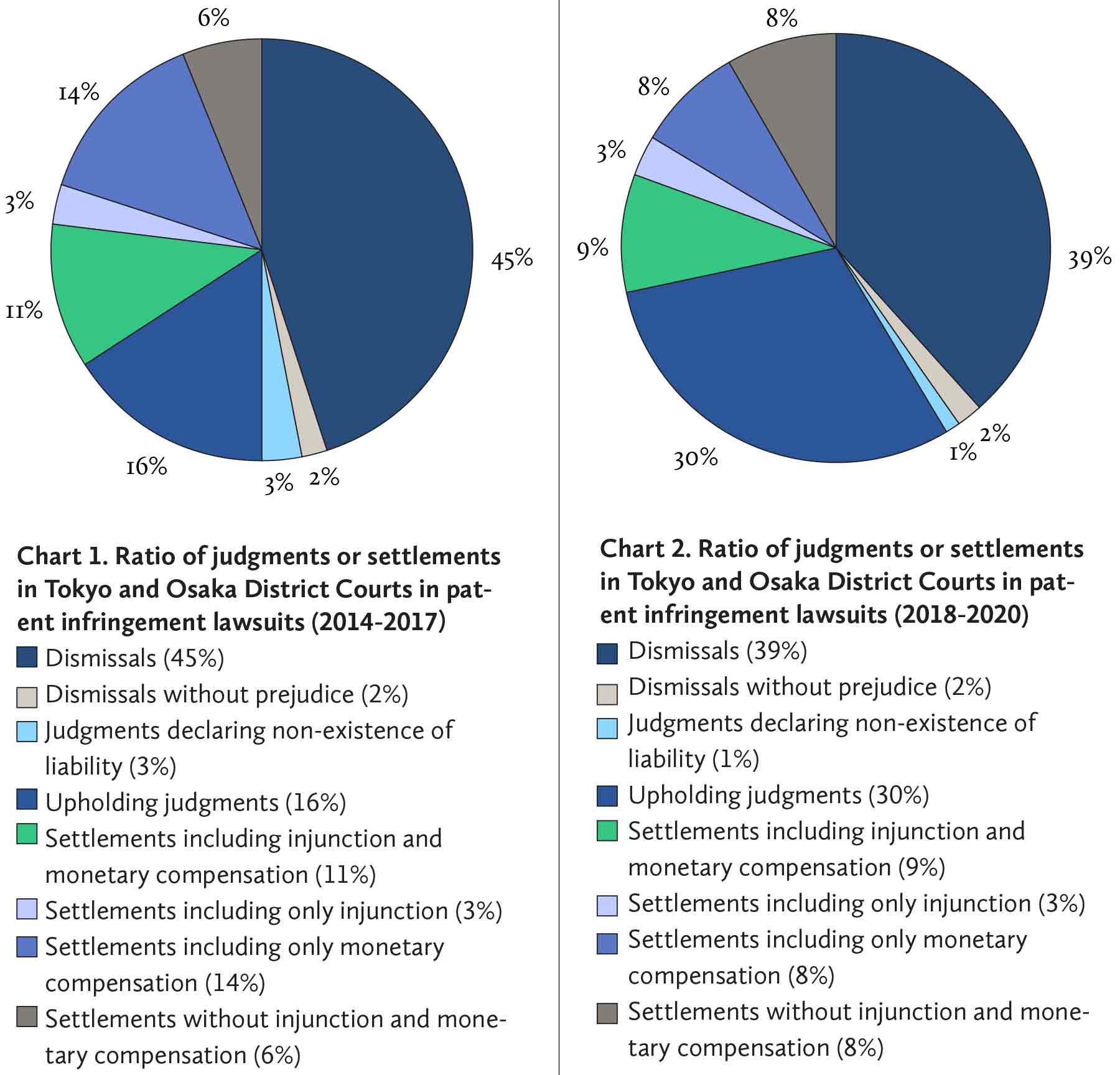

The charts below are based on the differences between two sets of statistics. Chart 1 shows the ratio of judgments by, or settlements in, Tokyo and Osaka District Courts from 2014 to 2017, and chart 2 shows the ratio from 2018 to 2020. They clearly show that the winning rate of patent owners has significantly increased recently.

The percentage of upholding judgments was 16% from 2014 to 2017, but it drastically increased to 30% from 2018 to 2020. Also, the ratio of dismissals was 45% from 2014 to 2017, but it dropped to 39% from 2018 to 2020. Notably, many settlements are favourable for plaintiffs, so the substantial winning rate for patent owners is much higher than 30%.

This clearly shows the recent pro-patent tendency of Japanese judges. Now it is much easier for a patent owner to win an infringement lawsuit than before, and it is very difficult for an accused infringer to defend themselves successfully.

Increase in compensation

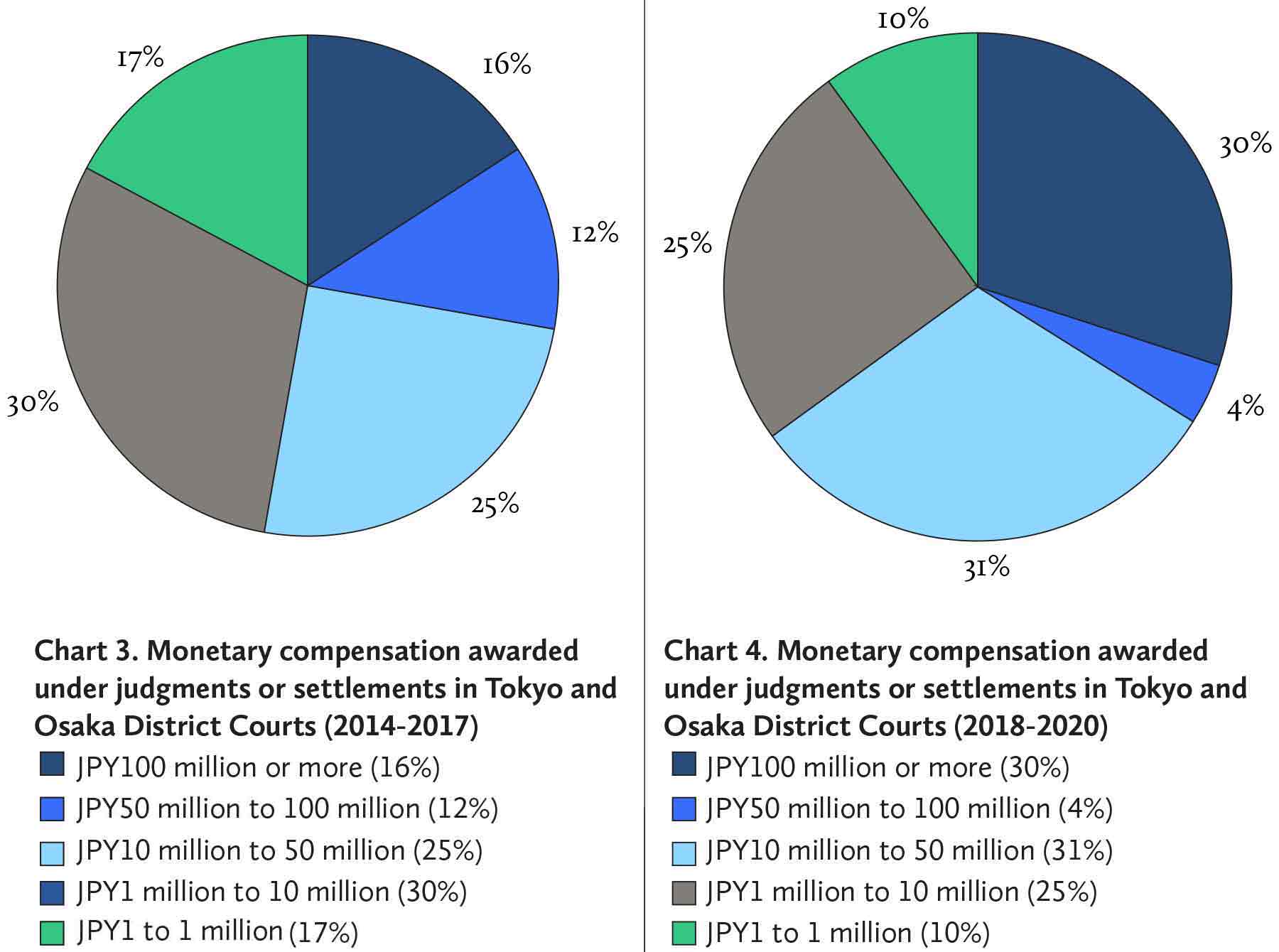

The amount of monetary compensation has increased in the past few years. Chart 3 shows the ratio of each amount of monetary compensation awarded under judgments by, or settlements in, Tokyo and Osaka District Courts from 2014 to 2017, and chart 4 shows the ratio from 2018 to 2020.

Significantly, JPY100 million (USD887,900) or more was awarded only in 16% of cases from 2014 to 2017, but that increased to 30% from 2018 to 2020. Also, JPY10 million or more was awarded in 53% of cases from 2014 to 2017, but that has increased to 65%. The ratio of payments less than JPY10 million dropped from 47% to 35%.

These data clearly show that the monetary compensation amounts awarded in judgments and settlements have been increasing recently.

The grand panel decisions of the Intellectual Property High Court in 2019 and 2020 have shown its intention to increase damages amounts, and Japan has amended its Patent Act to increase presumed damages amounts. The above data show that the monetary compensation amounts awarded in judgments and settlements have increased.

Influence of pro-patent tendency

The data show that Japanese patent rights are much stronger now. This change has been rapid and significant, and the value and risks of Japanese patents are different from a few years ago. But the change is as yet not well recognised.

Japan is now an attractive option for a company choosing a jurisdiction to file a patent infringement lawsuit. The Japanese court system has special divisions that handle only IP cases, and the judges are specialised and skilled in patent litigation. Besides, they have tended to decide for patent owners in close cases recently, as the data show. Patent infringement lawsuits in Japan are a reasonable choice for companies that actively use their patents to gain profits.

At the same time, patent infringement risks are greater now. Unlike the US, Japanese courts grant injunctive orders without additional requirements if there is a patent infringement, and this may have a critical impact on companies’ business in some circumstances. In addition, the damages amounts are tending to be larger. Accordingly, a careful risk evaluation, such as free-to-operate research and patent invalidity evaluation, is highly important when conducting business in Japan. In some circumstances, a re-evaluation of patent infringement risks is recommended, considering the recent pro-patent tendency.

OHNO & PARTNERS

21/F, Marunouchi Kitaguchi Building

1-6-5, Marunouchi, Chiyoda-ku

Tokyo 100 0005,

Japan

Tel: +813 5218 2331

Email: ohnos@oslaw.org

Malaysia

The covid-19 pandemic affecting the world’s population has demonstrated the importance of advancements in medical technology and securing patent protection in countries of interest. The ongoing debate concerning the waiver of the enforcement of the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement in 1994 for all IP related to the prevention, containment and treatment of covid-19 has brought up the age-old question of striking a balance between greater public access with the aim of global vaccinations and the rights of the patentee.

Due to the territorial nature of patent protection, substantial emphasis is placed on registering patents in all countries of interest. In times of a resource crunch, patentees must be strategic about how funds are utilised. Malaysia, a developing nation that is a signatory to major international IP treaties, has patent laws and procedures that reflect the trends in the global patent sphere. It is worthwhile to note that the system in place, either through the Malaysian Patents Act, 1983, or the various international treaties and agreements, supports expedited examination and unhampered enforcement even during times of a pandemic.

Malaysia’s patent system

As a signatory to the Patent Co-operation Treaty (PCT), Malaysia benefits applicants that seek international patent protection by providing a unified procedure for patent applications across its contracting states. Patentees are thus able to seek patent protection in other member countries simultaneously. Malaysia is a participant in the Asean Patent Examination Co-operation (Aspec), the first regional patent work-sharing programme among nine states’ IP offices including Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. This programme is aimed at reducing duplication of work that needs to be carried out by each participating patent office by sharing search and examination results between them. The participating patent offices gain by saving valuable time and resources, while patentees benefit from faster and more efficient patent prosecutions.

Partner at Skrine in Kuala Lumpur

Tel: +603 2081 3999 (ext. 736)

Email: co@skrine.com

Malaysia has also expedited patent examination procedures under the Patents Act, pursuant to the Patents (Amendment) Regulations, 2011. A patent applicant who has made a request for substantive examination may request the approval of expedited examination once the application has been made available for public inspection. This was introduced to reduce patent pendency by expediting and accelerating the allowance, issuance and grant of a patent.

The Intellectual Property Corporation of Malaysia (MyIPO), the patent office responsible for the provision of IP registration services and administration of IP registries, currently has patent prosecution highway (PPH) agreements with four foreign patent offices – the Japan Patent Office (JPO) since 2014, the European Patent Office (EPO) since 2017, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) since 2018 and, most recently, with the Korean Intellectual Property Office (KIPO) since 2020.

Under the PPH, a patent applicant may request accelerated examination by the MyIPO based on favourable examination results of a corresponding application in Japan, Europe, China, Korea or a PCT application. A notable feature of the PPH programme is its bidirectional nature, in that examination at the JPO, EPO, CNIPA or KIPO can also be accelerated based on favourable examination by the MyIPO of a corresponding application in Malaysia.

Partner at Skrine in Kuala Lumpur

Tel: +603 2081 3999 (ext. 853)

Email: kpy@skrine.com

Requests under the Aspec and the PPH do not require any additional official fees. For an Aspec request, the MyIPO may consider the search and examination results from the participating foreign patent office, but is not required to accept the results of such search and examination. The author’s experience under the PPH programme is that when the Malaysian claims conform to the foreign allowed claims, the Malaysian application will generally be accepted for the grant.

Besides the various partnerships and international affiliations, Malaysia has its own designated IP High Court, established in 2007. The court, situated in Kuala Lumpur, is a court of the first instance. Judgments from this court may be appealed to the Court of Appeal and, with the leave of court, to the Federal Court, the country’s apex court.

Enforcement during pandemic

The Malaysian courts, which usually conduct hearings and trials fully in-person, have adapted and adopted procedures to support remote hearings and trials. It is noteworthy that these virtual hearings and trials substantially reduce the costs of bringing foreign witnesses to Malaysia. This has proven to be a significant benefit, particularly for patent trials that require the evidence of experts from overseas.

The pandemic has certainly brought the question of waiver of patent rights to the centre stage, particularly with provisions allowing for compulsory licensing or government use of patents. Article 31 of the TRIPS agreement, which provides for compulsory licensing or government use of patents, is one of the more notable enforcement challenges patentees face, especially in lesser developed countries. Patentees in Malaysia are no exception, with local patent legislation implementing article 31, codifying it in part X and section 84 of the Patents Act. Part X provides for compulsory licence applications by private parties, while section 84 concerns government rights to the use of patents.

While article 31 and the act allow for the issuance of compulsory licences permitting the exploitation of patented products domestically, the amended article 31bis allows for compulsory licences permitting the export of patented pharmaceutical products from Malaysia. Article 31bis has not been codified into Malaysian patent law, but proposed amendments to the Patents Act and Patent Regulations, 1986 suggest that such applications may be possible in the future.

Compulsory licence, government use and safeguards

The MyIPO handles applications for compulsory licences under part X of the act. Section 49 states that applications for compulsory licences can only be made in either of the following circumstances:

- Where there is no production of the patented product or application of the patented process in Malaysia without any legitimate reason; or

- Where there is no production of the patented product for sale in any domestic market, or there is some production, but they are sold at unreasonably high prices or do not meet the public demand without any legitimate reason.

Section 84 of the Patents Act empowers the minister in charge of IP (i.e. the Minister of Domestic Trade and Consumer Affairs) to decide whether a government agency or a designated third party is permitted to exploit a patented invention without the patentee’s consent where:

- There is a national emergency, or where the public interest – in particular, national security, nutrition, health or the development of other vital sectors of the national economy as determined by the government – so requires; or

- A judicial or relevant authority has determined that the manner of exploitation by the owner of the patent or his licensee is anti-competitive.

To date, there have only been two published instances where section 84 was invoked – in 2003, in relation to three HIV/AIDS drugs and, in 2017, to permit the importation of generic versions of a Hepatitis C drug. In both cases, the government had first engaged in negotiations with the patentees, giving them the opportunity to make representations.

Section 84 contains certain safeguards that protect the interests of patentees. Notably, the Patents Act requires that patentees are notified of the minister’s decision “as soon as is reasonably practicable”, and section 84(3) further provides that patentees are to be paid an “adequate remuneration”, the amount of which is to be decided upon hearing representations by patentees and other interested parties (if they wish to be heard). Patentees may also request that the compulsory licence be varied or terminated, and the minister may so vary or terminate the licence after hearing the relevant parties.

Additionally, section 84 does not grant the government unlimited powers to exploit a patent, and all government use of patents is subject to the following limitations:

- The exploit of the patented invention is limited to the purpose for which it was authorised;

- Patentees are not excluded from exercising their patent rights; and

- The exploitation shall be predominantly for the supply of the Malaysian market (this limitation would not apply to article 31bis applications).

Patentees are also not left completely defenceless where the government exercises its rights, as section 84 explicitly provides that patentees may appeal to the high court against the decision of the minister. While article 31bis, compulsory licensing and government-use may cause concern to patentees, there are necessary safeguards in place to prevent abuse of such provisions.

Level 8, Wisma UOA Damansara

50 Jalan Dungun, Damansara Heights

Kuala Lumpur, 50490 Malaysia

Tel: +603 2081 3999

Taiwan

Taiwan has long been known for its advanced technological developments, including but not limited to those related to R&D and the integrated circuit (IC) supply chain. The rapid recent growth of technology has put Taiwan in the spotlight. According to statistics shared by Taiwan industry research institute DigiTimes, in September 2021, among the major Asian countries, only in Taiwan is the contribution of the technology sector exceeding 60% among listed companies. This fact demonstrates the importance of Taiwan’s technology industries. Behind the scenes, the related legal frameworks are fundamental to fuelling the accelerated yet stable development of both the capital and technology markets.

Senior Partner at Formosa Transnational in Taipei

Tel: +886 2 2755 7366

Email: yulan.kuo@taiwanlaw.com

Foreign stakeholders need to understand Taiwan’s patent laws, in addition to other types of IP protection available, for the purpose of doing business in Taiwan.

An introduction

Three types of patents available in Taiwan – invention, utility model and design patents.

An invention is eligible for patent protection if it is a technical creation that satisfies the requirements of novelty, non-obviousness and industrial utility. The term of an invention patent is 20 years from the date on which the patent application is filed. Extensions for the patent protection term are available for a pharmaceutical, agrichemical or manufacturing process, taking into account the time needed to obtain the required regulatory approvals.

A utility model is a creation made in respect of the form, construction or fitting of an object. The protection term for a new utility model is 10 years from the filing date.

A design patent is a creation made in respect of the shape, pattern or colour (or a combination of these) of an article as a whole or in part, by visual appeal. The protection term for a design is 15 years from the filing date.

Partner at Formosa Transnational

in Taipei

Tel: +886 2 2755 7366

Email: jane.wang@taiwanlaw.com

Taiwan’s patent regime is open to foreign nationals on a reciprocal basis. That is, foreign nationals may apply for patent protection as long as their home countries also make patent protection available to Taiwanese citizens.

Under Taiwan’s Patent Act, as long as a foreign company can properly establish that it duly holds a Taiwanese patent, the company does not need to have corporate recognition from the Taiwan government – which exists when a foreign company has a presence registered at Taiwan’s corporate registry – before it may seek remedies that are available to all Taiwanese citizens.

Taiwan’s Patent Act only provides civil remedies to patentees who discover that another is infringing their patents. If a patentee establishes that a third party is infringing his/her patent, the patentee may seek a court judgment that orders the infringer to cease the infringing activities, to destroy infringing products/articles and tools/equipment used in the course of the infringing activities, and to compensate damages that the patentee suffers as a result of the infringement.

The Intellectual Property Office

The Taiwan Intellectual Property Office (TIPO) has authority to examine applications and grant patents, as well as to review other applications in relation to patent protections. The TIPO also has authority to preside over invalidation actions initiated by a party seeking to invalidate a patent.

Partner at Formosa Transnational in Taipei

Tel: +886 2 2755 7366

Email: brian.hsieh@taiwanlaw.com

Parties who disagree with the TIPO’s rulings cannot seek judicial remedies against these rulings unless they first file appeals with the administrative appeal review board, and subsequently fail to obtain favourable rulings from the board. A proposed amendment to the related laws was published by the TIPO for public review and comments in 2020.

Under the proposed amendments, in most situations parties can directly go to the court if they do not accept a TIPO ruling in relation to a patent matter. It is believed that the amendments, if passed by the legislature, will substantially decrease the time needed to conduct and conclude invalidation actions and the subsequent appeal process.

The Intellectual Property Court

In 2008, Taiwan established the Intellectual Property and Commercial Court (IP Court), which exclusively hears and adjudicates IP matters. The IP Court enjoys non-exclusive jurisdiction over patent infringement litigation at the first instance, as well as exclusive jurisdiction over the same in the second instance. So, a party seeking to initiate patent infringement litigation against an infringing party can choose to so do before the IP Court, or before a district court that has proper jurisdiction over the matter.

All patent infringement litigation at the second instance, however, is heard only by the IP Court. Subject to some exceptions, most patent-related judgments of the IP Court at the second instance can be appealed to the Supreme Court, which will only review legal questions present in the judgments issued by the lower courts.

When presiding over a patent infringement case, an IP Court judge may appoint a technical examination officer, who will assist the judge to understand technical issues involved in the case. Most technical examination officers are senior patent examiners at the TIPO, and are experienced in, and familiar with, patent matters.

The officers usually sit in the courtroom and listen to the arguments of both parties to the patent infringement litigation. They may directly make inquiries of any of the parties when the judge deems the question raised is proper and necessary. With these officers’ assistance, it is believed that the IP Court judges are much better equipped to look into complicated technical issues present in patent matters.

Infringement civil lawsuits

While a party must still file an invalidation action with the TIPO if the party wishes to invalidate a certain patent, infringement litigants (usually the alleged infringers) can raise a validity defence against the patents that are the subject of the infringement litigations. When an alleged infringing party raises a validity defence, the IP Court will investigate the substance of the defence and consider whether or not the patent is valid in light of the challenges raised.

If the IP Court finds the patent to be invalid, it will rule that the patent is unenforceable, and will dismiss the patentee’s litigation claims. In other words, when a parallel invalidation action is filed at the TIPO, the IP Court hearing the civil infringement litigation will not wait for the TIPO’s ruling, but will determine the validity issue on its own.

According to data published by the IP Court, between the third quarter of 2008 and the second quarter of 2021, 50.69% of all first-instance patent infringement litigations where validity defences were raised were concluded with rulings that the patents were invalid and thus unenforceable. The data demonstrate that it is crucial for patentees to re-examine the validity of their patents before initiating infringement litigation. To prevail in patent litigation, the first step is to overcome anticipated challenges to the patent’s validity.

Claims for damages

A patentee may recover damages if he/she successfully establishes the infringement and also overcomes any validity challenge. Under Taiwan’s Patent Act, when asserting a damage claim, the patentee may calculate the amount of the damages by either: (1) the monetary amount of injury suffered and/or the loss of profits due to the infringing activities; (2) the amount of the benefits gained by the infringing party due to the infringing activities; and (3) the amount of a reasonable royalty fee that the patentee could obtain from the infringing party’s activities.

An enhanced damages claim is available when the patentee proves that the infringing party intentionally conducted the infringing activities. The enhanced damages cannot exceed three times the amount of the actual damages amount established by the patentee.

According to a study published by the IP Court, among all first-instance patent infringement litigations where the patentees prevailed, the IP Court has tended to grant damages close to the amounts requested by the winning patentees. It is also noted that a damages award of TWD2 billion (USD72 million) was granted in an IP Court ruling in a first-instance patent infringement litigation.

Disputes on repairs exemption

Recently, some high-profile IP Court rulings on design patent infringements have attracted substantial public attention. The debate focuses on whether the Taiwan Patent Act should include an exemption that makes vehicle maintenance/repair activities free from patent infringement liability.

Currently, there is no such exemption available under Taiwan’s Patent Act. While some advocate adding such an exemption into the law, others argue against this, explaining that Taiwan law gives judges discretion in making some necessary arrangements if they find it extremely inappropriate to grant to a patentee all remedies available at law. In 2020, several legislators proposed an amendment to the Patent Act to include an exemption for vehicle maintenance/repair activities. It would thus be prudent to monitor future developments in this regard.

FORMOSA TRANSNATIONAL

13/F, 136 Jen Ai Road, Sec. 3, Taipei

Tel: +886 2 2755 7366

Email: ftlaw@taiwanlaw.com

www.taiwanlaw.com