As part of our annual exploration of billing rates, we decided to begin analysing specific sectors for an insight into how fee practices vary. In this report, Luna Jin takes a close look at domestic capital markets and how legal service providers are quickly adjusting their pricing strategies to reap monetary rewards

WITH A SERIOUS WANE in international capital market activity, Chinese companies have gazed inward for opportunities with a friendlier fundraising environment on the horizon, and a consequent stampede of legal activity has followed.

Every law firm with a sniff of a chance at tender, it seems, has rallied to grab a slice of the pie as domestic IPO activity has outstripped offshore markets with all their risk and rancour.

Lawyers have been busy sharpening their competitive edges on multiple fronts for a fair share in this money market. The wave of interest has sparked escalating wars for top talent, with even wet-behind-the-ears new talent getting unprecedented offers.

Pitch after low pitch have clients in a prime position for price cuts on their legal fees, while some law firms struggle with manpower calculations and business overhauls to enable provision of anywhere near adequate services at low rates, and the hope of a mitigating bonus.

All of this is occurring at a point when regulatory reforms are enabling quicker capital access and the sector is poised for a full-on upgrade. If you see any downsides to these observations, you are on the money.

Now that the dominant fee structure in China’s legal market is “lump sum/contract price + bonus” – and this applies to the vast majority of transactions, as we have reiterated in our previous annual billing rates reports – law firms have found themselves in a race to not only win over the deal but also increase their traction in the market. Although hourly billing is accepted by only a limited number of international clients, or under special work engagements, we have continued to track the deomestic market for the sixth year and 26 leading domestic practices have disclosed their hourly rates for 2022 to China Business Law Journal. Please refer to the table on HERE for relevant data.

In order to better understand the considerations of both buy-side and sell-side for specific types of legal work, this year we focus on fee practices in the high-octane capital markets area. With feedback from in-house counsel and different types of law firms, we discuss the opportunities, dilemmas and prospects of the industry at a time when domestic and overseas markets have demonstrated contrasting performances in the past year.

Chinese companies’ traditionally brisk overseas financing activity dropped to its lowest point in 2022 amid international tensions, regulatory uncertainty and a global economic downturn.

The decline in the number of overseas projects in 2022, caused by a lull in both primary and secondary markets, led to “intensified price bidding among law firms”, says Huo Chao, a partner at Haiwen & Partners’ Beijing office. Haiwen is among the eight Red Circle firms that are perceived as leading practices in the country, and that dominate the overseas equity and debt capital markets (ECM and DCM) businesses, due to the high demand for lawyer reputation and capabilities in handling such transactions.

By contrast, the domestic capital markets paint a more vivid picture as they benefit from institutional regulatory reforms and the inevitable fundraising needed for China’s overall economic expansion.

Chinese companies have therefore turned to domestic markets, although seen as “settling for second best” by some, to fulfil their hunger for financing, making the domestic bourses exceptionally active since 2021. For the first three quarters of 2022, by accumulated funds raised via IPO, the stock exchanges of Shanghai and Shenzhen ranked first and second among their global peers, respectively.

Previously, the listing regime in China under an examination system was stringent and time-consuming, requiring those applying to issue securities to have their applications checked by regulators. By comparison, the registration system, although common in international practice, places an emphasis on information disclosure and naturally lowers the listing threshold. This is also a big reason why Chinese companies have always preferred seeking funds overseas.

As the Star Market, ChiNext and Beijing Stock Exchange consecutively adopt the registration system, the regulatory shift has been reflected in an increase in revenue for capital market lawyers.

Those law firms historically specialising in this area say legal fees as a whole have shown a year-on-year upward trend in the past three years.

According to market data (see table below) compiled and shared with us by Zhang Liguo, the Beijing-based managing partner at Grandway Law Offices, for a total of 65 listings on the main boards of the Shenzhen Stock Exchange (SZEX) and Shanghai Stock Exchange (SHEX) between January and November 2022, the average legal fee per listing was RMB6,863,000 (USD996,700), an increase of up to 25.4% compared with the average for the whole of 2021, while the average legal fee total per listing on the Star Market rose by 26.5%.

Zhang says that this is because the workload of lawyers has gradually increased based on the requirements of securities regulations such as the extensive shareholder verification work for pre-IPO services in recent years.

“With the gradual implementation of the registration system, lawyers are playing a more active role in capital market businesses, providing more in-depth and comprehensive services,” he says.

However, this trend has not been reflected equally across all sectors. Dorothy Xing, the managing partner of East & Concord Partners in Beijing, says the reality is that “lawyers’ fees are very much polarised and, in general, not optimistic”.

She says that companies in hot sectors are competing for excellent legal service resources and are willing to pay good money for them. On the other hand, “whether it’s IPOs or refinancing, legal service fees are quite low in traditional areas including a large number of main board projects, and the financial and manufacturing sectors; this year [2022] witnessed the lowest fees I’ve ever seen”.

But even in this buyer-driven market, companies are not just looking for low prices. Several in-house counsel also expressed their preference for high-quality legal services.

“Successfully completing an IPO is the primary goal of a company, and choosing a lawyer based merely on price is penny wise and pound foolish,” says the general counsel of a leading pharmaceutical company that has just completed an IPO.

INTENSE ‘INVOLUTION’

Leading partners and law firms, the pinnacle players in the capital game, receive big pay cheques as the necessary representatives of IPOs, an almost essential step for Chinse companies to expand amid the country’s economic growth. And so, impelled by opportunities for sizeable income, more law firms of varying expertise and scope are vying for a slice of the pie.

Low-price competition is a common occurrence. China Business Law Journal research has found that even established capital markets law firms have participated in price wars from time to time, which has allowed them to continue to consolidate their position in the game.

Cut-throat competition on the sell side does not necessarily always favour the client. On the contrary, it may even slow down a transaction.

One partner, who asks not to be named, says in many cases the clients suffer more than they gain if choosing the winning bidder based purely on price, where law firms only invest in very limited resources with junior staff and reduced service quality.

“Much of the work ends up being done by the client’s project team themselves, and they may even encounter price increases midway through the project,” he says.

In addition to market behaviour, the overall imbalance between supply and demand in China’s legal market contributes to low-price competition. “China’s legal workforce has expanded, but the market has not expanded proportionately,” says Xing. Ministry of Justice statistics show that by the end of 2021, there were about 575,000 practising lawyers nationwide, and this number has been growing at a rate of more than 10% every year since 2017.

“Changes in the number of lawyers and market capacity are not positively correlated and inevitably lead to a downward price squeeze, which is what we often call ‘involution’,” she says.

Involution has become a buzzword in China’s social media and a keyword repeatedly mentioned by interviewees that vividly describes the exceptionally competitive state of the Chinese legal profession.

The competition among law firms goes beyond competing for clients and starts at the talent recruitment stage. The lucrative work of capital markets lawyers naturally attracts top talent and firms compete for this cream of the crop.

In recent years, to ensure that graduates from top law schools are brought into the fold, entry-level salaries at Chinese law firms are gradually moving in line with those of international firms with a list of “30,000 yuan club” law firms, which offer a monthly salary of more than RMB30,000 for fresh graduates, being widely circulated.

The involution has not only driven the top partners in the elite niche of the profession to continue to improve their service capabilities, but has also brought some in-house counsel, albeit on the buyer side, into the race of broadening the boundaries of their knowledge.

Wang Xiaojing, the head of legal at China Nonferrous Mining Corporation, says that one of her company’s nine in-house counsel now has a CPA (certified public accountant) qualification, and three others are preparing for their CPA exam.

DO THE STRONG ALWAYS DOMINATE?

According to a legal research institute Wutongshuxia, as of 30 September 2022, there were 268 newly listed companies in the A-share market, with issuers paying a total of RMB1.68 billion in legal fees.

The top 10 law firms in terms of total fees were responsible for 165 of these companies (see table below). They are: Zhong Lun Law Firm, AllBright Law Offices, Grandway Law Offices, DeHeng Law Offices, JunHe, Shu Jin Law Firm, King & Wood Mallesons, T&C Law Firm, Jia Yuan Law Offices and Grandall Law Firm.

In a highly competitive environment, it is not easy for law firms to manage the cost and profitability of these capital markets projects, and each type of law firm has developed a variety of business strategies depending on the budget of its target client group, its industry position and the size of its business.

Some law firms reduce costs by doing projects on a large scale to make the work replicable. Among the above-mentioned firms both Zhang, of Grandway, and Yan, of Jia Yuan, mention an “integrated” approach to managing capital markets businesses, with clear fees and service standards, while Shanghai-based managing partner Charles Guan, of Grandall Law Firm, says when handling related work his firm adopts a “modular” management mode.

Zhang says that Grandway forms a multi-person team consisting of senior partners and front-line project lawyers to review the filing documents and working drafts, and to hold meetings to address important and difficult issues of the project, “effectively ensuring replication and passing down of knowledge and experience”. In addition, the firm has procured and customised a number of legal tools to improve efficiency for due diligence work.

Yan says that Jia Yuan has a sizeable capital market service team of more than 400 people mainly serving central enterprises, SOEs and defence enterprises. “We bank on expanding our business scale, doing a good job of maintaining existing clients and keeping total costs manageable, thus improving marginal revenue,” she says.

However, one partner, who asked not to be named, says that some law firms with A-share projects as their main business are maintaining profits by cutting costs of individual projects and taking on a greater number of them, meanwhile offering lower salary packages to lawyers or relying on replicable project experience and only staffing these projects with less experienced lawyers.

Law firms managed under a corporate model have generally distanced themselves from such a “quantity tactic”, placing greater emphasis on the co-ordination of resources across disciplines and geographies within the firm and the in-depth involvement of partners in cases.

Huo, of Haiwen, says that only a few of Haiwen’s 80 partners focus on capital markets work, so the average number of projects handled by each partner is constantly high, which is valued by many clients.

For law firms managed under the corporate model in China, such as Haiwen, partners are considered more prone to utilising internal recourses within the firm. By comparison, for team-based law firms with dozens or even hundreds of capital markets partners, one team is less willing to co-operate with another because it will have to share the revenue, and naturally each partner wouldn’t handle as many cases on average. Firms under the corporate management model also set up an internal assessment of the rate of return for each partner. The attractive entry salaries offered by some law firms, as mentioned above, are eventually reflected on the firm’s balance sheet, which means a significant fixed cost outlay, and this makes it impossible for partners to do too many low-price projects, and steers them towards the higher end of the client base who are generous with their legal budget and bring in good revenue.

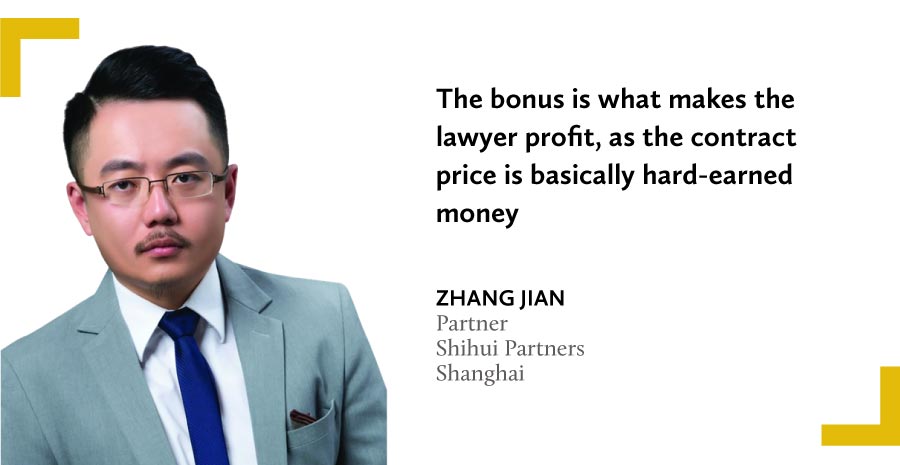

Some emerging law firms have chosen a path where they are willing to provide quality services regardless of cost, ceding some of their profits in the short term to build the firm’s brand. Zhang Jian, a Shanghai-based partner at Shihui Partners, explains that his firm is only six years old, insists on hiring top talent, and even offers some graduates an entry-level monthly salary of RMB35,000. “Better human resources will give a better customer experience, and ideally clients will be more willing to increase bonuses for us,” he says.

Some law firms are taking the opportunity to adjust their business and explore new ways of survival and prosperity. Xing, of East & Concord, says the firm’s original capital markets team has made a significant shift to public REIT projects in 2022, after weighing the high risk of IPO projects, and the firm’s Beijing office is working on more than 10 such projects. “With traditional IPO projects facing pressure on prices, and with too much competition, I’m glad to see that we’ve been able to find an alternative path of growth while maintaining our inherent market position,” she says.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.