How should Chinese companies determine their listing destinations when capital is tight at home and abroad amid new policies, Sino-US regulatory stand-offs and global geopolitical uncertainty? Sophia Luo reports

AS THE CORONAVIRUS PANDEMIC and escalating geopolitical storms have cast a shadow over the globe, China’s capital markets have followed a long, hard road since 2021. While opportunities like the newly minted Beijing Stock Exchange and a package of significant policies have been unveiled to deepen the opening-up and interconnection of markets, uncertainties including the twists and turns of global economic recovery and the US Federal Reserve’s consecutive hikes of interest rates have made positive progress challenging.

US-listed Chinese companies have come under the spotlight recently with the adoption of final amendments to the US government’s Holding Foreign Companies Accountable Act (HFCAA), 2020, in December last year. The law requires companies listed on US stock exchanges to declare they are not owned or controlled by the Chinese central government. With the final rules, the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has established a process by which it will impose trading prohibitions.

The HFCAA was introduced in 2020, and certain rules in 2021 amended the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. The amended Sarbanes–Oxley Act requires companies to disclose information on foreign jurisdictions that prevent the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board from conducting inspections.

The PRC regulatory regime for overseas issuance of listed securities was issued in 1994, revised in 2019, and supplemented by various rules that generally were still in draft form in 2021.

The SEC has been identifying affected issuers after annual reports were filed for 2021. Liu Zhen, head of the China practice and a member of Gunderson Dettmer’s global management committee, says the regulatory move’s significance is more evident in procedure than reality. She says the SEC’s list is predictable and it is too early to over-interpret the move.

Discussions over details of an audit deal between Chinese and US regulators have shown both sides are more willing to co-operate than be in conflict. The rhetoric is softening and there are prospects of reaching an agreement, says Liu. However, she advises relevant listed companies to maintain a clear mind and a sense of urgency.

Chinese companies traded in the US could face expulsion from US exchanges as early as 2024, after three consecutive years of non-compliance with audit inspections. Given that matching, adjusting and honing the two countries’ regulations and detailed provisions takes time, coupled with coronavirus pandemic challenges to the timetable for all cross-border collaborations, US-listed Chinese companies don’t have the luxury of time.

Won Lee, Hong Kong-based Asia capital markets team leader at Shearman & Sterling, says that, in addition to the HFCAA, there are other regulatory risks for US-listed China-based companies. On the US side it is heightened disclosures and, on the PRC side, increased regulatory scrutiny on “foreign” listings by China-based companies. Both continue to support a trend for “homecoming” listings of China-based, US-listed companies.

Lee says China-based companies that pose cybersecurity risks, or use variable interest entities (VIEs) face regulatory approval requirements that have made it almost impossible to list in the US. That has been a specific focus for the SEC, which has taken the extra step of requiring companies with operations in China (not only China-based companies) seeking to list in the US to disclose whether PRC regulatory approval is required and, if so, whether approval has been obtained.

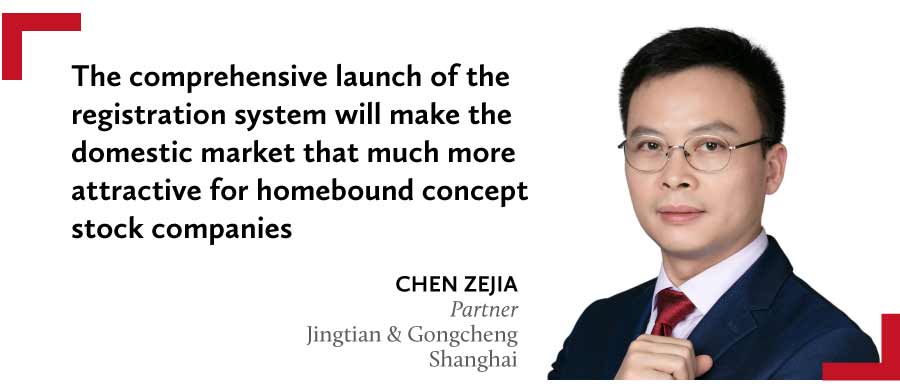

As for China concept stock companies already listed in the US, Chen points out that they should make preparations for a possible migration back to Hong Kong, or to alternative markets such as Singapore.

Lorna Chen, Asia regional managing partner, head of Greater China and a member of Shearman & Sterling’s executive group, advises companies to continue paying attention to key issues affecting the market.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

HOW TO HARNESS THE NEWEST EXCHANGE

Chen Yang, a Beijing-based partner at Han Kun Law Offices, uses three keywords – “activation”, “nurturing” and “linkage” – to summarise what the founding of the Beijing Stock Exchange means for the market.

The Beijing Stock Exchange is generally compared with the Star Market and the ChiNext Board, since all are pilot boards under the registration-based IPO reforms. In deciding which board would-be listed companies should choose, Chen says factors such as industry position, financial indicators, the time required for review, and market performance should all be considered.

Zheng Chao, a Beijing-based partner at Merits & Tree Law Offices, says that because the Beijing Stock Exchange offers the route to board transfers, would-be listed companies don’t need to make desperate attempts with undue haste, regardless of realistic conditions, to realise the dream of getting listed on the major boards of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges.

Pan Xinggao, a Beijing-based partner at Commerce & Finance Law Offices, underscores the Beijing Stock Exchange’s requirements for the asset scale of would-be listed companies, including a minimum of RMB50 million (USD7.5 million) in net assets at the end of the most recent year and a total minimum share capital of RMB30 million after listing.

Liu Wei, executive partner at Grandall Law Firm based in Shanghai, says the net profit of all 48 enterprises that have made debuts on the Beijing Stock Exchange throughout 2021 was more than RMB25 million, and for 43 companies was more than RMB30 million. That indicates that the listing threshold is higher in practice than in theory. (For example, companies with a profit of about RMB20 million are theoretically eligible for listing on the Beijing Stock Exchange.)

Pan stresses that “opting for a listing on the Beijing Stock Exchange requires the company to be equipped with business scale and a real need for floats, rather than just following the crowd. Otherwise, it will bear the risk of a listing failure and pay extra fees to professional agencies for listing services.” Even if they manage to get listed, the annual maintenance cost is not a tiny sum for a fledging small company, he adds.

Chen says that under the registration-based IPO system it generally takes no more than six months for the Star Market and the ChiNext Board to review and respond to pre-IPO enquiries. For the Beijing Stock Exchange, the time is no more than five months. Since the Beijing bourse has sped up the review process since March this year, its review cycle will be much shorter in practice.

But Chen says listing entities of the Beijing bourse must have been listed on the National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ) innovation board for at least 12 months. Therefore, it takes much longer for companies that have not yet been listed on the NEEQ innovation board to make their debuts on the Beijing bourse than on the Star Market and the ChiNext Board.

This year, Chen has noticed that many companies seeking listings on the Beijing bourse have withdrawn their applications over issues mainly involving internal financial control, industry position, business performance, operational compliance and reliability of information disclosure.

Gao Wei, a Beijing-based partner at Haiwen & Partners, sums up: “In terms of listing review, business operations [are] the foundation, financial figures are the objective record, and compliance sets the boundary. Would-be listed companies should kick off their listing procedures only when the necessary prerequisites are in place. Especially for companies that are earlier in their development stage, smaller in size and more innovative, the mindset of ‘giving it a shot’ should be avoided.”

Practitioner’s Perspective Article Series

How a compliance non-prosecution system benefits IPO planners

By Wei Tianhui, Shu Jin Law Firm

Legal internal control in listing compliance, corporate governance

By Han Xu and Hao Jingmei, Guantao Law Firm

New listing landscape holds opportunity for well-prepared firm

By Gao Wei, Haiwen & Partners

Overview of listing by way of M&A and reorganisation

By Ni Jieyun, Dentons China

Main boards: first choice for large, medium-sized enterprises

By Zhang Liguo, Grandway Law Offices

Avoiding risks to listing success from R&D co-operation

By Liu Tao and Huang Qingfeng, Commerce & Finance Law Offices

Transfer of Beijing-listed companies to other stock exchanges

By Li Shijia, Han Kun Law Offices

Securities firms can defend against investor suitability disputes

By Chen Zhuo and Zheng Yeye, Tian Yuan Law Firm

Explore more articles on Capital Markets ➜

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

Chen Yang, a Beijing-based partner at Han Kun Law Offices, uses three keywords – “activation”, “nurturing” and “linkage” – to summarise what the founding of the Beijing Stock Exchange means for the market.

The Beijing Stock Exchange is generally compared with the Star Market and the ChiNext Board, since all are pilot boards under the registration-based IPO reforms. In deciding which board would-be listed companies should choose, Chen says factors such as industry position, financial indicators, the time required for review, and market performance should all be considered.

Zheng Chao, a Beijing-based partner at Merits & Tree Law Offices, says that because the Beijing Stock Exchange offers the route to board transfers, would-be listed companies don’t need to make desperate attempts with undue haste, regardless of realistic conditions, to realise the dream of getting listed on the major boards of the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges.

Pan Xinggao, a Beijing-based partner at Commerce & Finance Law Offices, underscores the Beijing Stock Exchange’s requirements for the asset scale of would-be listed companies, including a minimum of RMB50 million (USD7.5 million) in net assets at the end of the most recent year and a total minimum share capital of RMB30 million after listing.

Liu Wei, executive partner at Grandall Law Firm based in Shanghai, says the net profit of all 48 enterprises that have made debuts on the Beijing Stock Exchange throughout 2021 was more than RMB25 million, and for 43 companies was more than RMB30 million. That indicates that the listing threshold is higher in practice than in theory. (For example, companies with a profit of about RMB20 million are theoretically eligible for listing on the Beijing Stock Exchange.)

Pan stresses that “opting for a listing on the Beijing Stock Exchange requires the company to be equipped with business scale and a real need for floats, rather than just following the crowd. Otherwise, it will bear the risk of a listing failure and pay extra fees to professional agencies for listing services.” Even if they manage to get listed, the annual maintenance cost is not a tiny sum for a fledging small company, he adds.

Chen says that under the registration-based IPO system it generally takes no more than six months for the Star Market and the ChiNext Board to review and respond to pre-IPO enquiries. For the Beijing Stock Exchange, the time is no more than five months. Since the Beijing bourse has sped up the review process since March this year, its review cycle will be much shorter in practice.

But Chen says listing entities of the Beijing bourse must have been listed on the National Equities Exchange and Quotations (NEEQ) innovation board for at least 12 months. Therefore, it takes much longer for companies that have not yet been listed on the NEEQ innovation board to make their debuts on the Beijing bourse than on the Star Market and the ChiNext Board.

This year, Chen has noticed that many companies seeking listings on the Beijing bourse have withdrawn their applications over issues mainly involving internal financial control, industry position, business performance, operational compliance and reliability of information disclosure.

Gao Wei, a Beijing-based partner at Haiwen & Partners, sums up: “In terms of listing review, business operations [are] the foundation, financial figures are the objective record, and compliance sets the boundary. Would-be listed companies should kick off their listing procedures only when the necessary prerequisites are in place. Especially for companies that are earlier in their development stage, smaller in size and more innovative, the mindset of ‘giving it a shot’ should be avoided.”

Practitioner’s Perspective Article Series

How a compliance non-prosecution system benefits IPO plannersBy Wei Tianhui, Shu Jin Law Firm |

|

Legal internal control in listing compliance, corporate governanceBy Han Xu and Hao Jingmei, Guantao Law Firm |

|

New listing landscape holds opportunity for well-prepared firmBy Gao Wei, Haiwen & Partners |

|

Overview of listing by way of M&A and reorganisationBy Ni Jieyun, Dentons China |

|

Main boards: first choice for large, medium-sized enterprisesBy Zhang Liguo, Grandway Law Offices |

|

Avoiding risks to listing success from R&D co-operationBy Liu Tao and Huang Qingfeng, Commerce & Finance Law Offices |

|

Transfer of Beijing-listed companies to other stock exchangesBy Li Shijia, Han Kun Law Offices |

|

Securities firms can defend against investor suitability disputesBy Chen Zhuo and Zheng Yeye, Tian Yuan Law Firm |

|