As part of broader efforts to revitalise the northeast rust belt in China, rejuvenation and reducing institutional rigidity has become a leitmotif for the region’s legal market. Winny Zhang reports

The importance of state-owned enterprises (SOEs) is underscored nowhere more than in northeast China. This was the birthplace of China’s industrialisation, and during the planned economy era it held a unique position as the torchbearer of heavy industry. The newly established leadership at the time regarded it as the “eldest son of the People’s Republic”, a title frequently used to denote SOEs.

However, following the reform and opening up policy, the northeastern region of China ‒ consisting of Liaoning, Jilin and Heilongjiang provinces ‒ has experienced a drastic decline in its contribution to the national GDP, dropping from 13% in 1978 to 4.8% last year. The region, once a thriving industrial hub, now bears an uncanny resemblance to the Midwest region of the US, earning it the moniker of “China’s rust belt”.

As a downstream industry that is heavily reliant on economic development, northeast China’s legal market has been persistently sluggish in terms of business quantity and service quality, and seems to be mired in a stagnant state that makes it challenging to foster new business growth. Nevertheless, there are glimmers of hope on the horizon.

In the first quarter of 2023, the economic growth rates in the region were: 4.7% in Liaoning; 5.1% in Heilongjiang; and 8.2% in Jilin. These figures surpassed the national average of 4.5%, indicating that the 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25) for Northeast China’s Revitalisation is on the right track.

The plan was approved by the State Council two years ago, and one of the key components involves promoting the development of private enterprises and reforming SOEs.

Some law firms are constantly monitoring the national policy’s overhaul of the corporate ecosystem, seeking opportunities for legal services resulting from institutional reforms. But they continue to focus on the traditional business of serving SOEs, and leverage their accumulated experience to cater to these regional mainstream enterprises, which have a unique corporate culture and differ from private enterprises. At the same time, they are paying attention to the development of private enterprises.

Despite for the most part not having the geographical advantages of coastal regions, the three northeastern provinces are located close to Russia, South Korea and Japan, which aligns with the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), extending the local legal market’s influence to northeast Asia.

While challenges persist in the northeast legal market, national law firms recognise its potential and are continuing to enter the market. But they are approaching with caution, considering the differences in the market brought about by the uneven regional development of the three provinces.

The trajectory of the northeast’s legal market mirrors that of the revitalisation programme. While it may be too early to predict the outcome, what is certain is that the rusty northeast is being polished and renewed.

State-run market

The prevalence of heavy industry in the northeast often creates the illusion that the size of SOEs across the region is significantly larger than those in the coastal areas. However, the reality is quite the opposite.

According to publicly available data, the total assets of SOEs in Liaoning were expected to reach RMB2.8 trillion (USD390 billion) in 2021, which is less than one-sixth of the total in Guangdong. Even Harbin, which has the highest figure for total assets of SOEs in the northeast, is only about 14% of the size of Guangzhou.

However, this does not imply that SOEs have lost their dominant position in the region. “The backbone of the northeast economy is SOEs, which further reinforces the non-market element of the legal services market,” says Zhao Tong, a senior partner at Jincheng Tongda & Neal (JT&N) based in Dalian.

“For instance, the government controls many of the legal services-related resources, giving it greater decision-making power over the selection and pricing of legal services,” says Zhao.

Private enterprises in the northeast continue to lag behind. According to the All-China Federation of Industry and Commerce, the three northeastern provinces combined hosted only seven of China’s top 500 private enterprises in 2021, which is three fewer than the 2019 figure and far less than the 51 based in Guangdong.

“Legal services from SOEs and the government still dominate a substantial share of the legal market in the northeast,” says Wang Zhe, a senior partner at Dentons China in Changchun. “The market potential is enormous and there is room for further exploration.”

This potential refers not only to the existing legal needs of SOEs, but also to new business generated by the requirement to enhance market competitiveness of SOEs outlined in the 14th Five-Year Plan for the northeastern region.

“Revitalising the old industrial bases in northeast China requires breaking through and reforming a lot of SOEs to integrate resources and promote new vitality,” says Yuan Feifei, director of the Changchun new district office at Gongcheng Law Firm.

The mixed-ownership reform in SOEs is a crucial step towards stimulating market dynamics. In 2021, the central government developed an implementation plan for this reform in the northeast, allowing enterprises to have capital from different ownership sources and replacing the situation where only state-owned capital is available for SOEs.

The pain of transformation has led to numerous restructuring operations. “Old SOEs need to be rejuvenated, adapt to market development and unload the burdens formed in history,” says Wang.

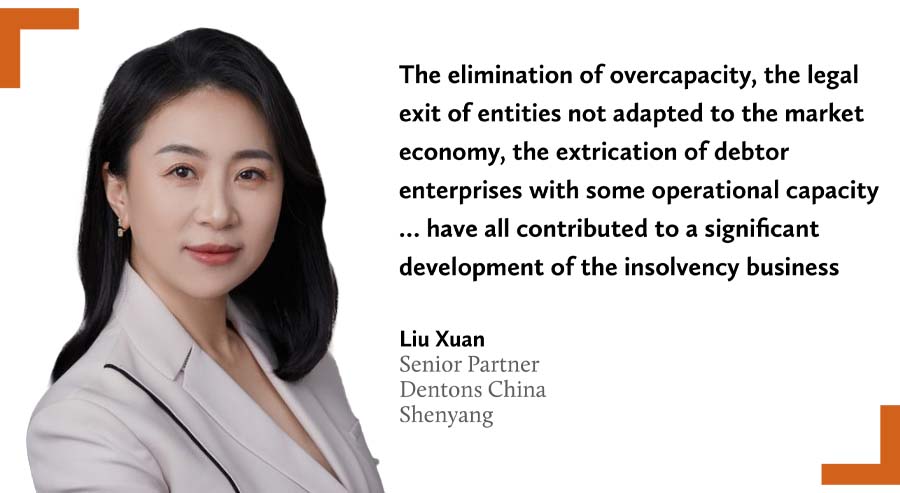

“But large SOE restructuring is complex,” adds Liu Xuan, also a senior partner at Dentons China but based in Shenyang. “Apart from being determined by market factors, the pivotal status of SOEs also determines their restructuring business and is to some extent influenced by the overall layout of the economy.

“So the restructuring business of large SOEs, though not rare, is not a common focus of the lawyers’ profession,” she says.

Liu says that the most active legal areas last year were compliance and insolvency. She says that since 2017 in Liaoning, there has been a surge of insolvency cases in line with the market-based and legalised insolvency scheme.

“The elimination of overcapacity, the legal exit of entities not adapted to the market economy, the extrication of debtor enterprises with some operational capacity, and the policy of guaranteed delivery of buildings have all contributed to a significant development of the insolvency business,” she says.

Amid the central government’s heightened focus on compliance, 2022 was designated as the “Year of Strengthening Compliance Management” for SOEs. Wang Enqun, the founding partner at Heng Xin Law Office in Dalian, observes: “Compliance-related legal services are a new area that law firms in the region are developing … Many law firms are developing compliance legal service products in areas such as anti-monopoly, anti-corruption, environmental protection and data privacy.”

Huang Xiaoxing, a partner at DeHeng Law Offices’ Shenyang office, predicts: “the corporate compliance sector may become a growth area for law firms in the future”.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.