Recent high-profile convictions are only one indication of a major crackdown on corruption. The challenge for domestic and foreign companies, and their advisers, is to establish a culture of corporate compliance

George W Russell reports from Shanghai

Wang Shouxin, a Communist Party official in Heilongjiang province, was publicly executed for corruption in 1980. She had embezzled about RMB500,000 from a local coal mine. A now-famous series of photographs, released only last year, showed her refusing to kneel before the firing squad until police kicked her legs from under her.

The 30-year-old photographs stirred up considerable public debate. Some people called for a return of public executions of corrupt officials. Others criticized the brutality of the system: Wang, they said, was surely a scapegoat for other, higher officials. For many, Wang’s behaviour before her death symbolized another problem: the defiance of those accused of graft.

Corruption has long been an issue in China but, as in Wang’s case, the highest-profile cases have historically occurred in the bureaucracy, the Party apparatus and the state sector. These cases continue. Wang Yi, a former vice president of China Development Bank, was sentenced to death (with a two-year reprieve) in April for taking bribes worth RMB12 million. Huang Songyou, the former vice-president of the Supreme People’s Court, was jailed for life for corruption in January.

But it is this year’s convictions of Huang Guangyu, the former chairman of private electrical goods retailer Gome, and former Rio Tinto executive Stern Hu, that have delivered a major shock to the global business community. The two cases have pushed corruption to the top of the agenda for both international and private domestic companies.

Hu was jailed for 10 years in April after a Shanghai court convicted him of taking kickbacks worth millions of dollars from Chinese steel firms and misusing company secrets. He and three other Rio Tinto employees had been arrested in July 2009 during contentious iron ore contract talks between foreign mining companies and the Chinese steel industry, sparking concern that the men were victims of political intrigue and anti-foreigner sentiment.

Much of the trial was held behind closed doors, which did little to allay fears that Hu wasn’t getting a fair hearing. Yet some independent experts deplored Hu’s supporters – especially the partisan Australian media—for their refusal to take account of the evidence against Hu and his co-defendants. “Some Australian newspapers cheered Stern Hu as a national hero,” says Liao Ran, Asia Pacific programme director at Transparency International, a Berlin-based anti-corruption watchdog which publishes an influential annual list of countries and their perceived levels of corruption. “That is quite incorrect.”

The Gome case, on the other hand, was a purely domestic affair. Huang, a high-school dropout who built a multibillion dollar retailing business from scratch, was sentenced to 14 years in prison and fined RMB600 million in May after being convicted of bribery. Gome’s illegal payments to officials totalled RMB4.5 million between 2006 and 2008, according to prosecutors.

Lawyers see the Hu case in particular as a wake-up call. “The Rio Tinto verdict, in which four executives of a high-profile international mining company were found guilty of bribery and theft of commercial secrets, may signal that China’s aggressive prosecution of its anti-corruption laws is shifting its focus to multinational companies operating on its soil,” notes Gary Anderson, a shareholder with Greenberg Traurig in Washington DC.

“Corruption continues to loom as a major political and economic challenge for China,” says Christopher Stephens, senior partner of the China offices with Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe in Hong Kong.

Turning the screw

Legally, Beijing has been tightening the screws on suspected bribery. In 2009, amendments to the PRC Criminal Procedure Law extended liability for corruption and bribery offences to the relatives of officials. The government also issued the Honest Practices in the Leadership of State-Owned-Enterprises Several Provisions in 2009.

Legislative reform has been accompanied by one of the most intensive crackdowns on corruption in recent memory. “We’ve seen spectacular crime-busting-style dawn raids on entire administrations,” says Andrew Halper, a partner at CMS, China. “They’re not just clamping down but smashing down on corruption.”

Lesli Ligorner, a partner at Paul Hastings Janofsky & Walker in Shanghai, notes that in many areas that might loosely be termed ‘compliance’, China’s laws have moved closer to international standards. “Cross-border compliance issues are occurring with increasing frequency as compliance with home country laws and regulations often overlap with compliance with local PRC laws and regulations,” she says.

Corruption and compliance: in-house or out?

When Scott Lane first began educating companies in China about the fight against corruption, he made much use of the term “red flag” , denoting a danger signal or a cause for concern. His students asked him why he was associating the term with such negative connotations, given that red flags flutter proudly over every Chinese city.

Lane believes he has cleared up the confusion – enough for him to name his Hong Kong-based, China-focused consultancy The Red Flag Group – but the initial puzzlement underscored the difficulties inherent in promoting the idea of “compliance” in Chinese corporate culture.

Lane’s company is one of a number of consultancies that are looking to exploit the potential of China’s emerging compliance market. “Much of our work is for large US-based multinational companies who are looking to improve their compliance infrastructure in emerging markets like China,” says Lane.

Specialist risk consultancies say they can offer a multi-disciplinary approach. “Very few companies are equipped to investigate fraud and corruption when they become its victim,” says Steve Vickers, president and chief executive officer of FTI-International Risk in Hong Kong. “Fraud and corruption is often complex, difficult to unravel, and handling it requires specialist knowledge.”

China is also attracting attention from another segment of the compliance industry, vendors of software and other products that support the human skills of lawyers and consultants. “We think China is our largest potential market,” says Woon-Kee Baeg, director of pre-sales and marketing at GT One Governance Technology, a Seoul-based outfit that sells software to monitor potential money-laundering activity.

Vendors meet resistance

One niche that outside vendors have managed to break into is databases. Dow Jones – the international media company owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corporation – offers three updated lists of potential money launderers: DJWatchList, DJSanctionsAlert and DJAntiCorruption. “China corruption-related work forms a lot of what we do,” says Richard Butler, a risk and compliance solution specialist at Dow Jones in Sydney.

However, many vendors and consultancies have met resistance from many companies, which believe that sensitive investigations and monitoring are best conducted internally. “There is a strategy of not airing dirty laundry among third parties,” says Violet Ho, managing director of the Beijing office of Kroll, the global risk consulting firm.

Companies, especially those conducting internal investigations into suspected corruption, have a tendency to maintain strict confidentiality. “In-house counsel’s value is knowing the business model, the jargon and the sensitivity,” says Erica Wang, general counsel at Eli Lilly in Shanghai. “Internal staff know the business and we can smell something fishy.”

Some internal counsel are even more appalled at the idea of “outsourcing” compliance-related investigations to external counsel or consultants. “Offshoring presents challenges,” says Patricia Sullivan, Asia-Pacific regional head of anti-money laundering and anti-bribery compliance at UBS Investment Bank in Hong Kong. “Certain control measures cannot be outsourced.”

Other corporate lawyers add that any kind of third-party offshoring would require regulatory approval from all the jurisdictions involved. “You would need local approvals and a real compliance risk management policy,” says Daniel Au, vice president and country anti-money-laundering manager for Deutsche Bank in Hong Kong.

However, small and medium sized companies might lack the resources to fund their own in-house compliance staff. Aub Chapman, a Sydney-based compliance consultant, says companies with as few as five employees have already fallen foul of Australia’s regulatory system. “Small financial institutions cannot afford to do this,” he says. “Outsourcing could be the only answer.”

Credibility and privilege

Lawyers acknowledge there are often issues of confidentiality and corporate secrecy involved in such investigations. But wholly in-house reports can have their own problems. “A company’s internal investigation might not be considered credible by governmental authorities,” says Peter Wang, a partner and head of the Shanghai office at Jones Day.

Major matters, Wang adds, would require the appointment of external lawyers. “You may need outside counsel to represent the company and independent board members may need to engage their own counsel,” he says. “The idea of using only in-house counsel goes out the window if it’s too serious.”

There are concerns relating to the extent of privilege applying to in-house investigations. “In Europe, there are issues concerning the extent to which in-house counsel have the benefit of legal professional privilege,” says Grace Ng, a consultant at Lister Swartz, a firm of Hong Kong solicitors in association with US-based Edwards Angell Palmer & Dodge. “[This] makes it highly advisable for investigation to be co-ordinated by external counsel.”

Law firms can draw on deeper levels of resources, lawyers point out. “In-house law teams are small and external law firms are large,” says Andrew Halper, a partner at CMS China in Shanghai. “We can do a lot of things and we can be an extra pair of eyes.”

Beatrice Schaffrath, a Beijing-based partner and a member of the China compliance practice at Baker & McKenzie, says outside counsel can fulfil a multitude of roles. “Our assistance includes structuring and conducting internal investigations, advising the company on its responses to government-initiated investigations and information requests, developing and implementing compliance programs, policies and training, and identifying and managing corruption-related risks.”

Enforcement remains inconsistent

Not all breaches of compliance regulations would have such severe repercussions as the Rio Tinto and Gome cases. “Such high profile cases are criminal cases and could be deemed as extreme cases,” says Kevin Xu, a partner at Martin Hu & Partners in Shanghai. “Many less serious cases need to be regulated by government or local administrative authorities.”

But some identify variable attitudes towards punishment as another problem. “China has extensive and stringent laws and rules against corruption, but uniformity and efficiency in enforcement is uneven,” says Stephens.

Others warn that anti-corruption purges in China can have a strong political element. “It is not necessarily the case that the recent high-profile anti-corruption cases have a corollary in an enhanced risk to our clients,” says Carl Hinze, an associate at Eversheds in Shanghai. “Nonetheless, if anti-corruption measures were ever diminishing as a concern for our clients, the recent cases have had the effect of bringing these issues to their attention.”

Both law firms and in-house counsel, say lawyers, will have to pay more attention to compliance issues in China. “High-profile cases such as Rio Tinto and Gome have forced foreign clients to become much more educated about local laws and regulations and to ensure that they are compliant,” says Chen.

Establishing compliance

One of the challenges in China—where gift-giving to cement business relationships is widely considered an acceptable practice—is to establish a culture of compliance that reaches to all levels of a company.

Compliance, it should be noted, means different things to different people. At its most basic, it simply means adherence to laws and regulations. In normal business usage, however, the term compliance is usually applied to a more limited – but still wide – range of issues, which might include competition laws, tax rules and labour and environmental standards as well as bribery and corruption.

Internationally, the term “compliance” has referred to a body of domestic and trans-national laws and standards applying to the prevention, detection and suppression of corruption and other white-collar crime. It has also covered related issues such as bribery and influence peddling and the diversion of money due to embezzlement, money laundering or the financing of terrorism.

Even the term “corruption” can be open to interpretation and reinterpretation. “Before 2001, Transparency International defined corruption as ‘misuse or abuse of public power for private gain’,” recalls Liao Ran. “Since then, we have defined it as ‘the misuse or abuse of entrusted power for private gain’. The international anti-corruption movement has expanded into the private sector.”

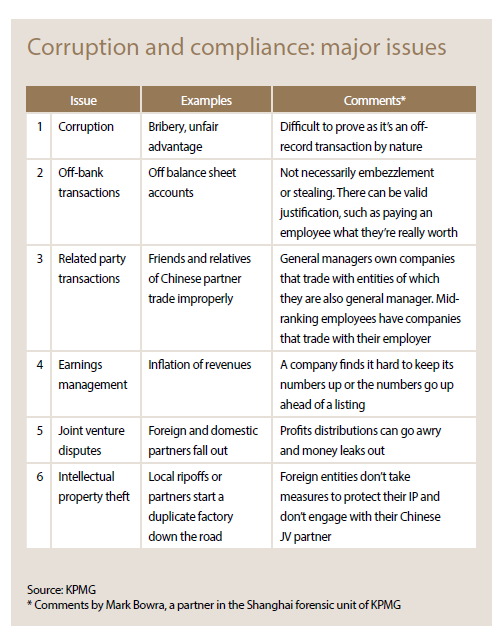

A major issue

Whatever the nuances of definition, the twin issues of corruption and compliance combine to pose a major issue for companies of all kinds. “Numerous companies do not have sound internal control systems and therefore are often exposed to potential risks. In addition, after the risks have occurred, those companies are inclined to rely on law firms or their internal legal departments,” says Zheng.

With businesses needing to ensure both external and internal compliance, a cottage industry of compliance consultants has emerged. Many multinational companies have established in-house compliance teams to work with senior management and corporate counsel. A large company such as Siemens, the German engineering group that has been dogged by corruption allegations for the past several years, has nearly 600 compliance officers worldwide, including 60 in China.

International law firms operating in China have raced to build practice groups to give compliance advice, while leading domestic firms such as King & Wood have begun to set up their own units (See Practitioner’s perspective, page 32). Paul Hastings Janofsky & Walker in Shanghai, for example, operates a dedicated China compliance unit. “Our advice spans issues such as corrupt payments to government officials, commercial bribery concerns, anti-unfair competition, kickbacks and other illegal sales structures,” says Ligorner.

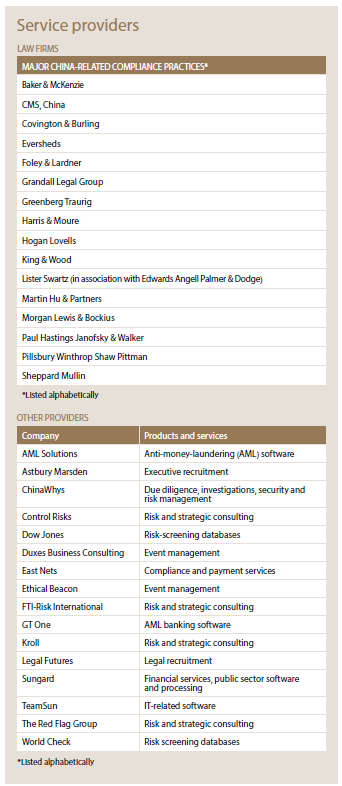

Such practice groups, in turn, may work with business and risk consultancies to provide advice, monitoring and training, while an army of private consultants, software vendors and other service providers have made an income from software, databases, filters and other products designed to augment human anti-corruption efforts. (See Service providers).

China compliance experts acknowledge that higher standards carry a cost. “You decide at what level of the corruption spectrum you want to be,” says Mark Bowra, a partner in the Shanghai forensic unit of KPMG, one of several global business consultants that have entered the compliance industry. “Being squeaky clean has business consequences,” he says. “It’s very much a commercial issue.”

Building a team

Compliance executives acknowledge that recruiting, nurturing and managing an in-house compliance team in China can be daunting. “This can be a difficult task that starts with gaining the trust of employees,” says Wan Kwong Wen, senior vice president and general counsel at Mapletree, a property and investment group based in Singapore. “Management must mean business in compliance and not only pay lip service.”

Recruiters say a certain amount of flexibility is required when hiring compliance-related legal staff. “We look carefully at technical skills, regulatory relationships, communication skills and comparable experiences with firms similar to the client,” says Julio Orr, a consultant with the Astbury Marsden recruitment company in Hong Kong. “Global institutions doing business in China still struggle to find the level of talent they are able to find in other more mature markets.”

Sales and distribution departments are among the most susceptible to corruption. Erica Wang, general counsel at Eli Lilly in Shanghai, tries to staff her compliance team with sales and marketing people to create integration between compliance and sales. “We look for people who have been ethical in past dealings and are close to our sales team,” she says. “Regional compliance officers are able to speak the same language as the sales team.”

However, some companies seem to struggle to shake off the curse of corruption allegations. Since 2006, Siemens, Europe’s largest engineering company, has been embroiled in cases concerning €1.3 billion (US$1.6 billion) in suspicious transactions, including in China. The allegations have cost the jobs of its chairman, CEO and other senior executives and the company more than US$1.6 billion in fines to the US and Germany.

Since then, Siemens has held itself up as a poster child for the compliance movement. Senior executives give lectures and attend conferences on compliance and the company is widely touted as a former offender that learned its lesson. “Siemens is now regarded as a benchmark in compliance,” says Zhao Aili, vice president and regional compliance officer with Siemens China in Beijing. “But we need to remain vigilant.”

Recent events suggest that such vigilance is justified. In April 2010, Chinese state media reported that Shi Wanzhong, an executive at China Mobile, China’s largest cellular-phone carrier, had been under investigation since December 2009 for allegedly accepting bribes from employees of Siemens.

Ben Wootliff, director of corporate inquiries in the Shanghai office of Control Risks, a London-based risk consultancy, wonders if repeat offenders should ask themselves hard questions about their future: “There’s enough research to show that if you have to pay bribes to keep going in business you have to ask yourself if you’re in the right business, or if you need a better business model.”

One more result of the crisis: a global compliance push

Lawyers say the financial downturn has turned corruption and compliance into live issues in many jurisdictions. “The global financial crisis has spurred many governments in the world to review and revise legislation concerning a range of compliance-related issues,” says Gary Seib, a Hong Kong partner and co-chair of the Asia Pacific compliance practice at Baker & McKenzie.

New anti-corruption legislation in China and overseas has encouraged companies to seek the services of law firms. “In recent years, there has been a greater emphasis on the enforcement of anti-corruption laws in numerous countries throughout the world,” says Gary Anderson, a shareholder with Greenberg Traurig in Washington.

One of the most recent pieces of legislation is Britain’s Bribery Act 2010. “This act represents a wholesale update of the antiquated and discredited UK bribery laws,” David Lawler, a partner and forensic accountant at Forensic Risk Alliance in London, noted in a recent assessment, referring to a previous patchwork of legislation that included the Public Bodies Corrupt Practices Act 1889, the Prevention of Corruption Act 1906 and the Prevention of Corruption Act 1916.

The British act contains extra-territoriality provisions similar to that of the United States Foreign Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 (FCPA), considered by many to be the grandfather of modern anti-corruption legislation. The FCPA was amended in 1998 to cover foreign firms and persons within US territory after the signing in 1977 of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions.

The FCPA is one of the more stringent anti-corruption laws among major economies, with five China-related enforcement actions each in 2008 and 2009. “There are serious consequences for lapses in compliance,” says Jonathan Polk, a senior vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York. “There are direct consequences, such as fines, penalties, lawsuits and restrictions, and there are indirect consequences such as damage to reputation as a result of a major compliance problem.”

China has always been fertile ground for FCPA prosecutions: In April, Avon Products, a US maker of beauty products, announced it had made an internal report available to US authorities in connection with bribery allegations concerning is China unit. In March, German car and truck maker Daimler agreed to pay US$185 million to settle charges by the US Justice Department and Securities and Exchange Commission over gifts to Chinese and other foreign officials to win business deals.

In other recent cases, US company Lucent Technologies resolved FCPA investigations in 2007 by paying a US$2.5 million fine, while Oregon-based metal recycler Schnitzer Steel paid more than US$15 million in fines and other penalties in 2005 because of kickbacks to Chinese mills and Texas-based GE InVision (now GE Security), a manufacturer of bomb detection equipment, paid more than US$1 million in fines in 2004 for FCPA violations in China.

The US regime has often been foremost in the minds of companies when devising compliance strategies. “Until recently, our clients had been focused on foreign anti-corruption rules,” says Peter Wang, a partner and head of the Shanghai office at Jones Day. “The thinking was that if they comply with US laws, the Chinese laws will take care of themselves.”

However, China has also developed its own laws and regulations to enhance supervision of compliance. “The recent issuance of the notice relating to enforcement of the commercial bribery rules signals that the government is more focused on enforcement in the commercial setting,” says Meg Utterback, managing partner of the Shanghai office of Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman.

Christina Wu, an attorney with Capital Law & Partners in Shanghai, cites the State Council Securities Companies Supervision and Management Regulations and the China Securities Regulatory Commission Securities Companies Compliance Management Tentative Provisions as examples. “There will be further compliance rules applicable to state-owned enterprises and listed companies,” she adds.

The Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the Ministry of Public Security issued a joint document in May, stating that non-government personnel who accept bribes of more than RMB5,000 will be subject to criminal prosecution.

In addition, recently issued regulations make companies responsible for the actions of agents. “It is not good enough to say ‘we don’t know what our agents are up to’,” says Violet Ho, managing director of the Beijing office of Kroll, a global risk consultancy.

The government has also rolled out an anti-corruption hotline and website to allow anonymous reporting of corruption issues. “It has very recently expanded the scope of a publicly accessible database of companies that have been convicted of bribery offences,” says Eric Carlson, an associate at Covington & Burling in Beijing. “All of this means that there is a greater likelihood of improper conduct being reported and prosecuted.”

Several prosecutions have resulted from Internet users highlighting abuses of power. Zhou Jiugeng, the head of a district property management unit near Nanjing, was prosecuted in 2009 after photographs of his expensive Cadillac car and Vacheron Constantin watch were posted online.