Shanghai is gearing up to offer new funding opportunities. But how close is it to becoming a world-class legal, trading and financial centre? By Robin Weir

A month before the World Expo 2010 opened to the public in Shanghai, Zhao Jiaoli, secretary general of the Shanghai Consumers Association, announced that a team of volunteer lawyers from leading law firms in Shanghai had been formed to help mediate consumer disputes at the Expo park.

If its organizers were expecting trouble, the word on the street a few weeks after Expo opened is that they got it. The official Shanghai Expo website reports that visitor numbers have grown steadily from a slow start. But some visitors still report poor organization, with long queues lasting for hours, and ugly crowd behaviour. Expo has cost twice the amount spent on the Beijing Olympics. The result, it appears, may be only half as good.

That’s not the picture many people have of Shanghai, which likes to project a rather more self-confident image of itself.

But with the national government keen to deflate China’s property bubble, and double-dip jitters in the wider global markets, do the troubles at Expo point to a less swaggering future in China’s number one trading port and financial market?

Global by 2020

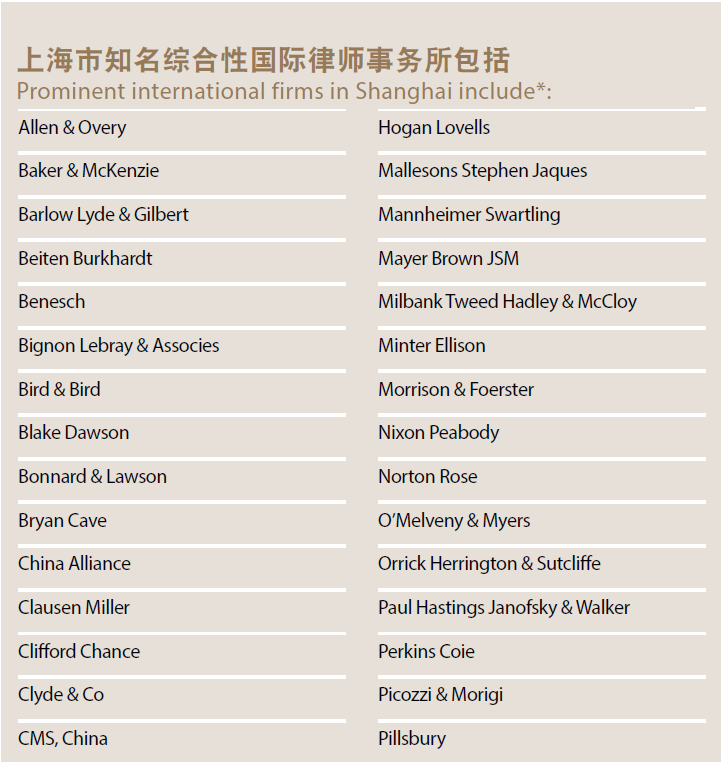

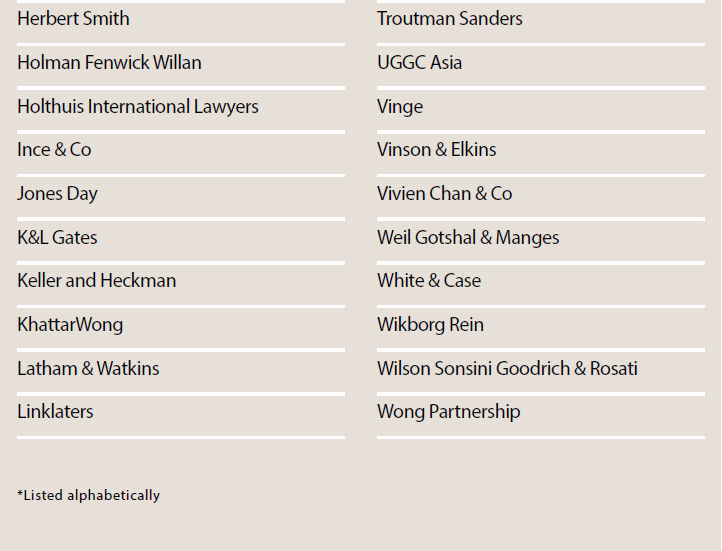

In April 2009, the State Council outlined its plan to make Shanghai both a global financial and shipping centre by 2020. “Of course, the convergence of finance and shipping is nothing new, as evident in cities like New York, London and Hong Kong,” observes Daniel Roules, a partner at Squire Sanders & Dempsey in Shanghai.

Gluck also notes that in 2009, the government introduced a number of policies aimed at regulating RMB settlement in cross-border trade. In one such policy, Shanghai, together with Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai and Dongguan were designated pilot areas for the use of RMB settlement in cross-border trade with Hong Kong, Macau and ASEAN countries. “Companies in these pilot areas have the option to use RMB for customs declaration and settlement of import and export transactions,” she says.

Listings for foreigners

But while these developments are certainly worthy of note, it is the internationalization of the Shanghai Stock Exchange which gives capital markets lawyers in the city dreams of world dominance.

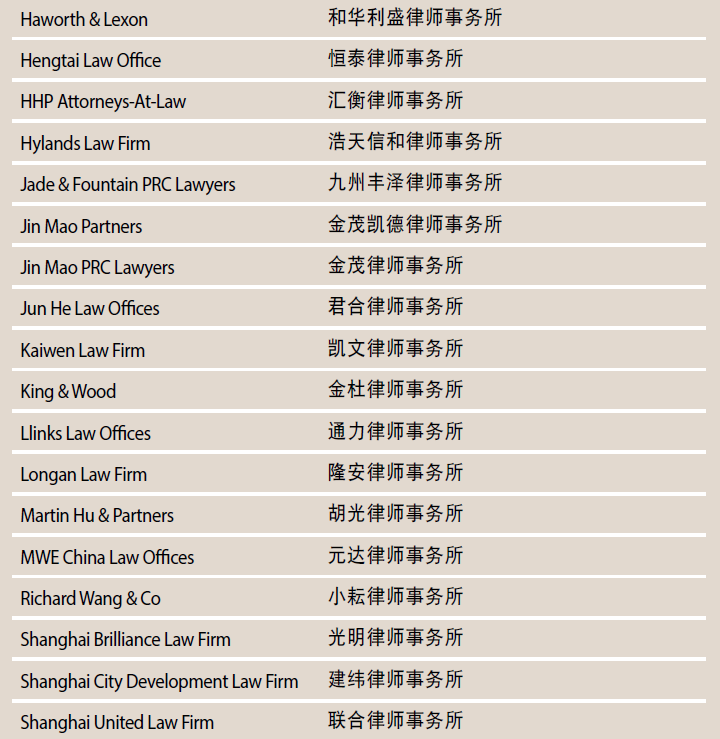

Most widely anticipated has been the expected launch of the international board, to which Shanghai hopes to attract international companies to list. “Different departments of CSRC have been working on this together with the Shanghai Stock Exchange, and all major issues have been cleared, including the disclosure rules, the accounting rules, and how to deal with the discrepancies between the Shanghai Stock Exchange and London or New York,” says David Dali Liu, a partner at Jun He Law Office in Shanghai.

Richard Xu, founding partner of Han Yi Law Offices in Shanghai predicts that the international board will be launched within two years. “Its launch will lead to the welcome return of top-quality red chips to China, and may also attract some foreign blue chip stocks,” he says.

And multinationals such as HSBC and others appear to be looking seriously at the possibility of raising cash by listing on the international board. “Some of our clients have already expressed an interest in a Shanghai listing,” says Heiner Braun, a partner at Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer in Shanghai.

Yet while CEOs across the world dream of getting their hands on the RMB that is stuffed into mattresses up and down the nation by listing on the international board, a parallel move is afoot to allow foreign investment enterprises in China itself – as PRC legal entities – to list on the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s main board. “There was no rule to prohibit this in the past, but it was not the policy or practice,” says Liu at Jun He. “But it has been hotly debated, and is to be expected soon.” Liu points out a number of obstacles still to be overcome, including foreign exchange issues and the question of how the foreign parent company’s information should be disclosed. “They still need to work out some supplemental rules,” he says.

Malta makes its name at Expo

“Chinese people know about Malta. They’ve heard of it,” Alan Camilleri, executive chairman of Malta Enterprise told China Business Law Journal.

For a small country in the Mediterranean Sea, with a little over 400,000 citizens, that’s not a bad start. And more Chinese people had heard of Malta after the opening ceremony of the Shanghai World Expo. The country’s president, George Abela, slipped and fell on his way to breakfast at a Shanghai hotel on the day of Expo’s official opening ceremony, suffering a hairline fracture to a vertebra. President Abela was admitted to Ruijin Hospital in Shanghai, then flown back to Malta on a medically equipped aeroplane provided by the Chinese government.

Abela and his entourage were in Shanghai for a reason. Trade between the two countries doubled between 2005 and 2008. In 2009, Malta was the only European Union nation to increase trade with China, with a 9.7% increase.

As the president had flown home, China Business Law Journal spoke instead to Alan Camilleri, executive chairman of Malta Enterprise – the agency responsible for the promotion of foreign investment and industrial development in Malta. Camilleri emphasized the advantages to Chinese investors of Malta’s membership of the European Union and the Euro zone, and its geographical position between Europe and North Africa. “Malta is attractive as a manufacturing base for a Chinese company that wants to access either the EU or the North African market,” he said, describing setting up in Malta for these reasons as “near-shoring”. As a full EU member, Malta does not, presumably, qualify as an “offshore” jurisdiction (see China Business Law Journal volume 1 issue 3, Paradise lost? China gets tough on offshore structures).

Nonetheless, Malta can offer an English-language environment, a favourable tax regime and labour costs which Camilleri estimates at 60% of the European Union average. According to Karl Xuereb, Malta’s ambassador to China, Malta was the first European state to register Chinese-owned ships, in 2001. The Malta Financial Services Authority (MFSA) recently signed a memorandum of understanding with The China Securities Regulatory Commission allowing Chinese Qualified Domestic Institutional Investors to invest in Malta-domiciled investment funds, and giving MFSA-registered companies Qualified Foreign Institutional Investor status.

Another area of growth is education. “A good number of Chinese students are already studying in Malta for degrees which are conferred by UK universities such as the London School of Economics and Royal Holloway,” said Camilleri. “You can study in Malta at roughly 60% of the costs you have to incur if you are living in the UK.”

Shaken, not stirred

While Shanghai’s equity markets are poised to go where no Chinese equity markets have gone before, the bond market is also becoming a key part of the funding mix for companies and, more recently, banks themselves. After allowing companies to issue short-term notes in May 2005, in 2008 the People’s Bank of China allowed the issue of such notes in the interbank market.

This has been followed by a move to open the door more widely to foreign banks. The first licence granted to a foreign bank to issue RMB-denominated bonds in China was, according to Wang of Broad & Bright, issued to Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi UFJ at the end of last year. The bank finally issued a RMB1 billion financial bond in the interbank market in May. “It is foreseeable that more and more foreign-invested banks or even foreign enterprises will look for financing opportunities in the PRC bond market,” says Wang.

Liu notes another associated change. “The interesting development will be this: to allow foreign-invested financial institutions to undertake such business as underwriter. This is still on a trial basis, but we expect that it will be open to all foreign-invested banks to act as underwriter.”

Funds wait for change

And the world of venture capital and private equity is also changing. As reported in China Business Law Journal in February, the Establishment of Partnership Enterprises in China by Foreign Enterprises and Individuals Administrative Measures, which came into effect on 1 March, allowed foreign investment without Ministry of Commerce approval for the first time. But the Measures came as something of a disappointment in private equity and venture capital circles, as they specifically excluded from their remit partnerships whose primary business was investment.

Nonetheless, progress is being made in Shanghai. In particular, the government of Pudong New Area has allowed foreign investors setting up venture capital funds there to take up to 50% of a limited partnership, and also to overcome some of the foreign exchange issues that have hampered their attempts to set up VC funds elsewhere in China. “The Pudong government pushed very strongly and got special approval from the State Administration of Foreign Exchange to allow settlement of foreign exchange into RMB,” says Liu.

Many lawyers remain cautiously optimistic about the future for private equity and venture capital. According to Anthony Zhao, a partner at Zhong Lun Law Firm in Shanghai, it is “inevitable” that “PRC-related fund activities will move more and more onshore, including fund raising, investment and exit”. Bernd-Uwe Stucken, greater China managing partner at Salans in Shanghai, believes that if and when the foreign-invested partnership structure becomes available to foreign investors to establish RMB funds, the result will be a significant movement of foreign private equity money into China. But he cautions that the government is “moving ahead with smallish steps, which is not untypical for China when venturing into untested terrain”.

Henry Liao, managing partner of Yuan Tai Law Offices, notes that the current Securities Investment Fund Law has been in force for six years – a long time in PRC jurisprudence – and expects a “breakthrough” in the near future. His analysis is that the fund industry’s “hands and feet are firmly bound, and it is urgently waiting for them to be loosened” . He believes that the question of whether to bring private equity investment funds within the scope of the Securities Investment Funds Law, thereby creating a unified funds law, is a “key question in the amendment of the current Securities Investment Fund Law about which there are differences and debate between various parties, and about which at present there is no unified official view”.

Hot property

On a Shanghai street, however, the topic of conversation is less likely to be of the capital markets than of property prices. According to Frank Chen, managing partner of Chen & Co Law Firm in Shanghai, prices have “increased noticeably” over the past year. Chen says speculative buying has been fuelled by “a combination of relaxed lending requirements, low interest rates and an inflow of investment from the government’s stimulus package”.

But as the heat of summer has intensified, prices have already started to cool. This is attributable, in no small measure, to what Chen calls “a number of familiar policy measures”, including the imposition of more stringent requirements on purchasers, a rise in the percentage of the purchase price required as a down payment, a moratorium on the purchase of second homes, higher transfer taxes and the introduction of a minimum period that a property must be held for before it can be sold.

As reported in the last issue of China Business Law Journal, many of these policy measures were contained in the Resolutely Halting the Overly Rapid Rise of Urban Property Prices in Certain Cities Notice, issued by the State Council on 17 April (see Government moves to control property market, China Business Law Journal Volume 1 Issue 5).

The 17 April Notice followed earlier notices from both the State Council and the Ministry of Land and Resources. But according to many lawyers, these notices mark just the beginning, not the end, of government efforts to tame the property sector. William Mo, a partner at Dacheng Law Offices, expects a number of further regulatory developments, including reforms to the taxation of property and to the way in which land is auctioned and granted, and stricter criteria on loans to property development companies.

William Soileau, a senior associate at Pinsent Masons in Shanghai, lists a number of measures his firm expects to see in the medium to long term. As well as new property taxes, a tightening of credit and new moves against speculation, Soileau expects that developers will face tougher land acquisition procedures “to ensure full pricing and fair compensation to relocated individuals”, increased scrutiny of project and planning approvals “to prevent a glut in luxury apartments and encourage construction of affordable housing,” and the tightening of construction, planning and environmental standards “to improve quality of the projects and raise barriers to entry”. For listed developers in particular, he foresees increased scrutiny of their balance sheets with particular regard to the valuation methods they employ.

Taking a broader view of efforts to cool the property market, Soileau also predicts the “liberalization of individual offshore investments as an escape valve for domestic hot money,” and the reform of local government finances “to wean local government from property development as a main source of revenues”.

Lawyers from outside Shanghai also offer interesting suggestions. Linda Tan of Kingson Law Firm in Guangdong believes that further revisions may be made to the PRC Land Administration Law, affecting the procedures for expropriating land and the rules governing the transfer for construction purposes of land owned by rural collectives. “The revision of the Land Administration Law will undoubtedly have a number of social effects, among which the impact on property developers will be the most obvious,” states Tan.

And Rocky Lee at Cadwalader Wickersham & Taft believes that the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) is taking an activist role in the regulation of real estate investment trusts (REITs). Lee points to a draft regulation entitled Administration of the Business of Real Estate Unit Trusts Tentative Measures, which has been jointly drafted by the CBRC and the People’s Bank of China to regulate the issue, transfer and liquidation of REITs.

VAT on property, and more?

A common conclusion among lawyers who have contributed to this article is that tax is a significant tool in the battle against real estate inflation.

More broadly, some lawyers point out that plans for the further development of the national VAT regime was announced in the State Council’s legislation plan for 2010. According to Francisco Soler Caballero, head of the Shanghai office of Spanish firm Garrigues, one possible change to existing VAT rules contained in provisional legislation may be an expansion of the scope of activities which are subject to the tax. In particular, VAT may be extended to items such as service income, which are currently subject, instead, to business tax. Soler believes this would bring China into line with other jurisdictions, and could also benefit some as the VAT rate is currently lower than that of business tax. “Service industry… could be further boosted,” he comments.

Chiomenti also expects that the scope of VAT is set to be enlarged, collection improved, and business tax gradually rolled into the VAT regime. The firm also notes that as VAT is paid to central government, while business tax is a local tax, a core issue of the forthcoming reform of VAT could be competition between central and local government over who gets the revenue.

Challenge and optimism

Many of the lawyers who have shared their opinions with China Business Law Journal on Shanghai and its future have sounded a note of caution among the lists of goals and achievements.

Roules of Squire Sanders & Dempsey notes that Shanghai “continues to follow the practices and concepts developed elsewhere rather than serving as an innovator of financial services”. He believes China should be more flexible in allowing professional services companies to establish operations that “support the development of sophisticated financing practices”, and points to a hedge fund client which is reconsidering a decision to establish a research office in Shanghai “because there is at present no form of entity that allows it to perform such research except with special licensing and higher capitalization”.

Wang of Broad & Bright sounds a similar note, stating that in comparison with the world’s other financial centres, Shanghai still has “much to learn”.

Anthony Root, managing partner of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy in Beijing and Hong Kong, notes that the largest cross-border, and particularly outbound, deals are coming from Beijing. He concedes that the commercial and financial work available in Shanghai may be a “more mixed and broader blend than you would find coming out of Beijing”. But he says that “until they allow foreign investors to invest freely in the Shanghai markets the way they can in the Hong Kong markets, I think it is going to remain more of a domestic financial centre than an international financial centre”.

Michael Wadley of Blake Dawson in Shanghai notes that while the city’s markets are big when measured by certain capital criteria, they are “still infants in modern financial history, tightly controlled in terms of banking access and very immature in terms of the consumers and players” . While state planning and controls can be a strength in troubled financial times, he says, they are “not seen as an attraction in comparison to more developed financial centres”. And Ulf Ohrling of Mannheimer Swartling in Shanghai is one of many who note that the current lack of convertibility of the renminbi is an obstacle still to be overcome. Other obstacles on Ohrling’s list are a “robust and transparent regulatory regime creating a level playing field between Chinese and foreign enterprises,” and “freedom of information” .

But despite the reservations, the mixed reports from Expo and the jitters in the property market, the overall mood remains upbeat. King & Wood, one of China’s top domestic law firms but which to date has been centred on Beijing, is investing heavily in its Shanghai office.

Frank Chen at Chen & Co states that Shanghai has a “relatively responsive” local government which “listens closely to the business and investment community, works to enact policies that attract businesses and enable growth, and strives to keep procedures and administrative matters transparent”. China Business Law Journal looks forward to watching the real Shanghai show, long after the Expo site is abandoned to rats and weeds.

Perfect legal system due this year

The State Council says Shanghai will be a global shipping and financial centre by 2020. Do government-imposed deadlines produce better results than government-built tourist attractions?

Xie Ying, an associate in the Beijing office of Italian law firm Chiomenti Studio Legale, reminds us that China long ago set 2010 as the deadline to complete the formation of a legal system with Chinese characteristics. The deadline was first set in 1997 at the 15th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party, and was re-confirmed by Wu Bangguo, the chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, in June last year.

With lawmaking authorities tuned into the rhetoric from the centre as the year rolls by, the team at Chiomenti, led by partner Gianluca D’Agnolo, believe that “many developments in PRC law and the legal sector” can reasonably be anticipated.

There is a widespread feeling, however, that progress at this time may take the form of consolidation, rather than a flood of new law. Jeffrey Blount, a partner in the Beijing and Hong Kong offices of US firm Fulbright & Jaworski, expects more active enforcement of existing laws, rather than the enactment of major new ones. “I believe we will see much more activist enforcement in areas such as tax audits and compliance, antitrust enforcement, securities regulatory enforcement, and media and internet licensing and of course, anti-corruption compliance,” he says.

Diaz Reus & Targ, which has an office in Shanghai, also foresees an increased compliance burden on both financial institutions and other companies (see Are you compliant?). This is at least partially a result of government efforts to combat money laundering. Vincent Li, an associate at the firm, noted that while the PRC Anti-money Laundering Law was promulgated in 2006, work in this area has been given new impetus by the publication in December 2009 of the People’s Bank of China’s first anti-money laundering strategy. The adoption of the strategy coincided with the issuance by the Supreme People’s Court of a judicial interpretation on money laundering, which extended criminal liabilities relating to transactions (including banking transactions) involving unlawfully obtained funds. “We foresee that more regulations will follow … that might potentially impact banks, trusts, investment funds, insurance companies, securities transactions, and non-financial institutions such as money transmitters and service providers,” says Li. He concludes that in-house counsel in both financial and non-financial institutions “must keep abreast of new developments and be prepared for compliance”.