Just as the Inuit people have many terms for describing different types of snow, the Chinese have many terms for describing the different documents that fall within the category of “written law”.

This can be a challenge to both legal translators and lawyers as they try to understand how the different documents fit within the legal and institutional hierarchy in China and also how the various terms should be translated into English. This column outlines the hierarchy in relation to the relevant issuing bodies (legislative and executive) and the legal effect of these documents, and sets out the standard way in which the terms tend to be translated into English.

It also highlights some of the points to bear in mind when dealing with the English names of written law in common law jurisdictions.

Generally speaking, there are two sources of law and regulation in the PRC: the legislative organs (also known as the “organs of state power”: 国家权力机关) and the administrative organs (行政机关).

Under the constitution of the PRC, ultimate legislative power is vested in the National People’s Congress (NPC) and its Standing Committee. The powers of the NPC include enacting and amending basic laws (基本法律) governing criminal offences, civil affairs, the State organs and other matters. The permanent body of the NPC, the Standing Committee, has the power to enact and amend laws (法律), with the exception of those that should be enacted by the National People’s Congress.

Further down the legislative hierarchy are local people’s congresses at various levels, which may adopt and issue local regulations (地方性法规) within the limits of their authority as prescribed by law.

Ultimate administrative power is vested in the State Council. It has the power to adopt administrative measures (行政措施), enact administrative regulations (行政法规) and issue decisions (决定) and orders (命令) in accordance with the constitution and other laws.

The various ministries and commissions under the State Council have the power to issue orders (命令), directives (指示) and rules (规章) within the jurisdiction of their respective departments and in accordance with law and the administrative regulations, decisions and orders issued by the State Council.

Further down the administrative hierarchy are local people’s governments, which may issue decisions (决定) and orders (命令) within the limits of their authority as prescribed by law.

Broadly speaking, therefore, written law in the PRC falls within, or derives from, the following two categories: (1) laws (法律) enacted by the NPC; and (2) administrative regulations, decisions and orders issued by the State Council (行政法规、决定、命令). At the very top, of course, is the constitution, which provides that no laws or administrative or local regulations may contravene the constitution.

The above categories are further expanded in the PRC Legislation Law. One of the objectives of the Legislation Law is to standardize legislative activities, the scope of which extends to “the enactment, revision and nullification of laws, administrative regulations, local regulations, autonomous regulations and separate regulations”.

The Legislation Law identifies the following additional categories of written law:

-

- local regulations (地方性法规), which are issued by the local people’s congresses or their standing committees;

- autonomous regulations (自治条例) and separate regulations (单行条例), which are issued by people’s congresses of the national autonomous areas; and

- local government rules (地方政府规章), which are issued by the people’s governments of the provinces, autonomous regions, municipalities directly under the central government and the comparatively larger cities.

The Legislation Law also mentions legal interpretations (法律解释) issued by the Standing Committee of the NPC, which have the same effect as the laws enacted by it.

It should be noted that although there are no constitutional or statutory provisions to the effect that judicial interpretations issued by the Supreme People’s Court (最高人民法院司法解释) have the same effect as laws, statements issued by the Supreme People’s Court assert that this is the case.

In terms of their effect, the hierarchy of the different types of written law in China is as follows:

-

- the constitution (宪法) has the highest legal effect;

- laws (法律) have higher legal effect than administrative regulations (行政法规), local regulations (地方性法规) and rules (规章);

- administrative regulations (行政法规) have higher legal effect than local regulations (地方性法规) and rules (规章);

- local regulations (地方性法规) have higher legal effect than local government rules (地方政府规章); and

- local government rules (地方政府规章) issued by the people’s governments of the provinces or autonomous regions have higher legal effect than the rules issued by the people’s governments of the comparatively larger cities within the administrative areas of such provinces and autonomous regions.

In passing, it is useful to note that the Legislation Law also confirms the two principles to be applied in resolving inconsistencies between written law in China; namely, (1) special provisions prevail over general provisions; and (2) new provisions prevail over old provisions.

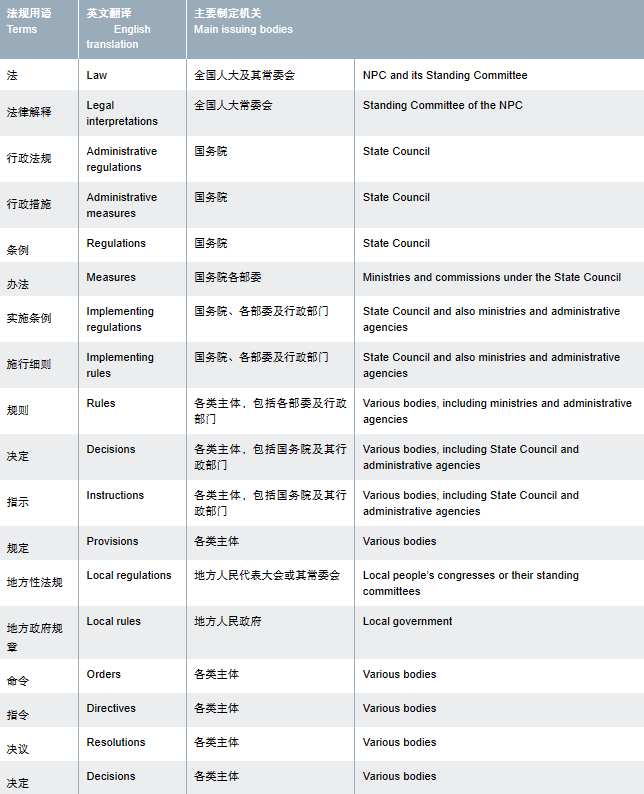

The following table sets out some of the different terms that are used to describe written law in China and the English translations that are most commonly used. It also identifies the main issuing bodies as suggested by a review of various legislative databases.

With limited exceptions (such as Hong Kong, where statutes are referred to as Ordinances), the terms used to describe written law in common law jurisdictions are relatively standard and straightforward.

There are a few points to bear in mind:

- the term “law” can be used either to refer to law generally or to refer to a statute;

- the term “legislation” is a generic term for written law enacted by Parliament (i.e. statutes or “Acts of Parliament”);

- the term “delegated legislation” refers to written law that is made by government agencies under power delegated to them by statutes; and

- as is the case in China, there are a number of terms used to describe delegated legislation. These include the following: (1) regulations; (2) rules (which are usually procedural in nature); and (3) by-laws (which can also be used to describe rules or regulations adopted by a company or an organization for its internal governance).

Under the PRC Legislation Law, in accordance with the relevant content requirements, legislation may consist of parts (编), chapters (章), sections (节), articles (条), paragraphs (款), subparagraphs (项) and items (目).

In relation to legislation in common law jurisdictions, the ordering tends to be as follows: chapters, parts, sections (these are used in place of articles, the use of which tends to be limited to articles of association or articles in international treaties), subsections, paragraphs and subparagraphs.

The term “clause” tends to be used more for contracts than for legislation and the term “provision” is used generically to refer to the content of both contracts and legislation.

A former partner at Linklaters Shanghai, Andrew Godwin teaches law at Melbourne Law School and is an associate director of its Asian Law Centre.