India’s once-vibrant capital markets have dried up. With the help of local and international lawyers, private equity is stepping into this financial desert to quench the corporate thirst for funds

George W Russell reports from Bangalore

Given the buffeting from the global credit crisis, the subsequent slump in initial public offerings and foreign currency convertible bond issues, and India’s already byzantine barriers for companies seeking domestic bank loans, it’s hardly surprising that private equity – the guardian angel or enfant terrible of the global finance system, depending on your point of view – is making huge strides on to the Indian stage.

“Private equity provides a very direct and accessible route to capital,” says Glenn S Gerstell, managing partner of the Washington office of Milbank Tweed Hadley & McCloy. “Private equity financing – by the nature of the deal-sourcing process – has the potential to drive increased levels of corporate governance and transparency, and can unlock and create enhanced business values through creative deal structuring and financial engineering.”

Moreover, Indian investors see a much-needed alternative to the costs involved with bank finance or an initial public offering (IPO). “Private equity is more flexible and adds international experience and credibility to the investee, which enables better valuations in case the promoters still wish to pursue an IPO, and has yielded very high returns to several investors as the Indian economy opens up,” says Anand Desai, managing partner of DSK Legal in Mumbai.

Major players seek attractive returns

From Wall Street’s heavy hitters to niche players from remote Iceland, foreign private equity funds are pouring cash into the Indian economy at an unprecedented rate. “While Indian markets have also undergone a correction, economic growth in India remains strong,” observes Yash Rana, a partner at Goodwin Procter in New York who has worked on several India-related private equity deals. “Therefore, private equity investors are looking to India as a source of attractive returns.”

The latest addition is legendary buyout firm Kohlberg Kravis Roberts (KKR), which announced in February that it would open an office in India, two years after its first deal, the purchase of an 85% stake in Flextronics for US$900 million. It will join Goldman Sachs, Warburg Pincus, Blackstone Group Holdings and The Carlyle Group, among others, in having a significant physical presence in India.

The previous month, Morgan Stanley Private Equity said its new Indian business would begin investing a total of US$1.5 billion from May 2008. The investment bank named Aluri Srinivasa Rao, formerly of ICICI Venture, as the head of its Indian investments. In July 2008, CDC Group, a British fund of funds, announced its US$185 million commitment to six India-specific private equity funds, while Utrecht-based Rabobank Group said it was launching a US$100 million India private equity fund.

These announcements followed several significant developments in 2007. In November, Reykjavik-based Askar Capital announced plans to set up a US$500 million fund focused on Indian small and medium-sized enterprises. Soon after, MPM Capital, a US fund, said it would tap its US$550 million Bioventures fund for India investments. In August 2007, the India Infrastructure Fund (run by India Infrastructure Finance Co and 3i) announced a target size of US$1 billion. Grant Thornton, a global consultancy, reported that in 2007 Indian companies received US$19 billion in private equity capital, compared with US$7.9 billion in 2006, US$6 billion in 2005 and US$1.1 billion in 2004. Over the past 12 months, Blackstone has paid US$116 million for 50.1% of India’s largest garment exporter, Gokaldas Exports; 3i’s India team has invested about US$100 million in real estate, media, automotive parts, infrastructure, power and ports; and Dubai-based Baer Capital Partners, co-founded by Michael P Baer of the Swiss family that founded Bank Julius Baer, launched its Beacon India Private Equity Fund.

Law firms join the action

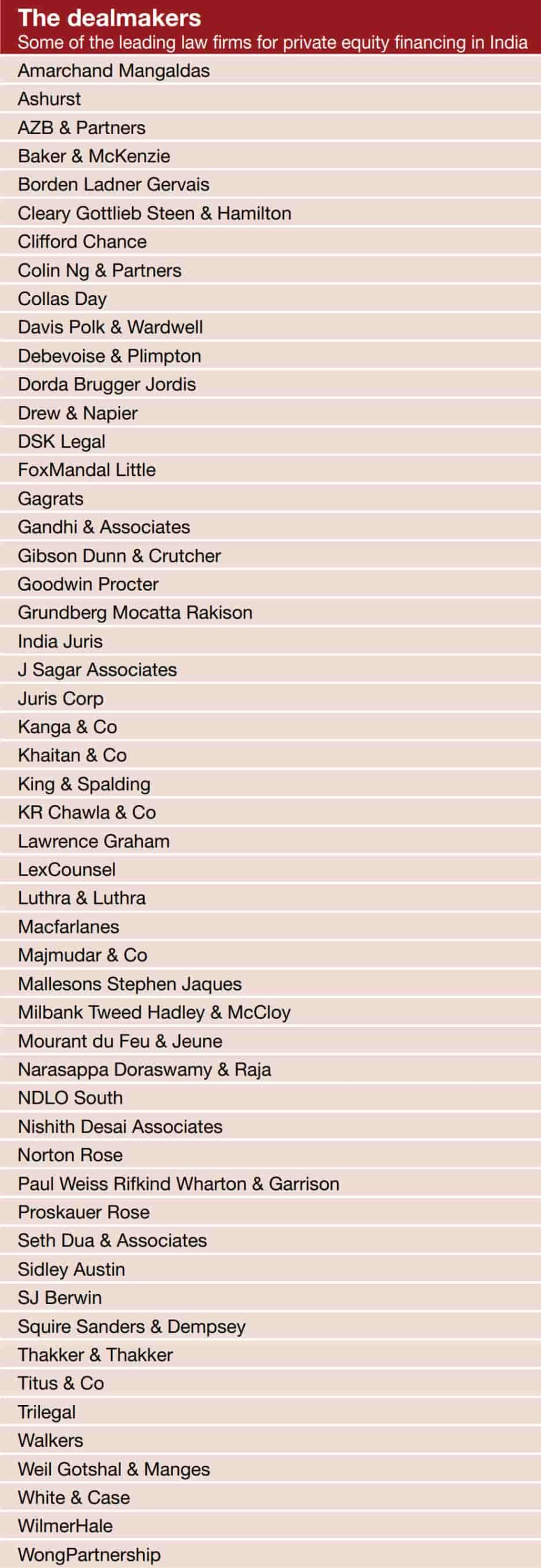

With all this India action, it’s no surprise that law firms – Indian and international – are gearing up to meet the growing demand. In July, Sidley Austin named Jason Tzucheng Kuo as one of four new Asia-Pacific partners. Kuo has worked on a broad range of private equity matters in India and elsewhere in Asia. The firm also hired Barry Breen in London, who has worked on private equity vehicles investing in infrastructure and green-field projects in India and Brazil.

Gibson Dunn & Crutcher expanded its Indian private equity capabilities with the hiring of India-qualified Jai Pathak and three other partners for its new Singapore office. Weil Gotshal & Manges, meanwhile, hopes that Hong Kong can serve as a springboard into India (as well as China and Southeast Asia) for its private equity clients, which include Providence Equity Partners, Bain Capital, CCMP Capital, Goldman Sachs and TH Lee Partners.

Private equity is part of the cross-border transactional work at Macfarlanes, which says it is building contacts in India, China, Russia and South America. Its clients include Alchemy Partners as well as 3i. India’s FoxMandal Little also advised Alchemy Partners in its formation of the Alchemy Partners AA Development Capital India Fund with the Ashmore Group.

Other international firms involved in recent India-focused private equity deals include Debevoise & Plimpton, King & Spalding and Mourant du Feu & Jeune, which advised DE Shaw & Co, Eastgate Capital Group and ICICI International respectively. Active Indian firms include Gagrats (advised Somaiya Group), KR Chawla & Co (India China Pre IPO Equity (Mauritius)), LexCounsel (Gaja Capital and Lakshya Interactive), Luthra & Luthra (Quatrro BPO Solutions) and NDLO South (HSBC Private Equity Advisors (India)).

Capital inflows accelerate

“There is an order of magnitude change in terms of the influence private equity will have,” Renuka Ramnath, managing director and chief executive of ICICI Venture Funds Management, told a Delhi private equity conference in March. She expects US$500 billion in inbound private equity investments to enter India between this year and 2020.

Private equity investment in India is already set to top US$25 billion in 2008 and reach nearly US$50 billion in 2010, according to analysts’ projections. Private equity firms invested roughly US$2.8 billion in 77 Indian companies in the second quarter of 2008, compared to 74 deals totalling US$1.9 billion in the second quarter of 2007, according to Venture Intelligence, a Chennai-based private equity and venture capital research consultancy.

For the first half of the year private equity investors put US$6.3 billion to work. “With rising consumer spending and infrastructure investments, Indian companies are expanding rapidly,” says Venture Intelligence chief executive officer Arun Natarajan. “Private equity has emerged as an attractive option for companies which have rapid growth plans and are not yet ‘public-market-ready’.”

The interest in India is part of a wider romance with emerging markets generally. In 2007, 222 emerging-market private equity funds raised US$93.6 billion, compared with 209 raising US$69.3 billion in 2006, according to Preqin, a London-based private equity research consultancy. Steven Lichtenfeld, a partner at Proskauer Rose in New York, says that more private equity funds have been inquiring about investments in emerging markets such as India (as well as China, Eastern Europe, and Central and South America).

Economic imperatives are part of the reason: the stumbling US economy is expected to contract in the second half of 2008 with gross domestic product (GDP) growth of just 1.3%, according to the International Monetary Fund’s latest World Economic Outlook Update, published last month. The report noted that the economic output in Europe and Japan is also expected to slow. While emerging-market GDP will also ease off, the comparable figures are from 8% in 2007 to 7% in 2009.

Youthful ventures

Given the global heavy hitters involved in India’s private equity market, it’s no surprise that venture capital is seen as the younger, sexier, sibling, with its own street jargon like “angel investors”, “drive-by deals” and “full-ratchet provisions”.

Venture capital is generally used as a term for capital invested by an outsider in a new, small or struggling business. It’s often a high-risk strategy, with the investor taking no more than three to five years from investment to exit.

There are few significant legal or regulatory differences between venture capital and private-equity investments. However, foreign venture capital investors are exempt from the minimum capitalization limits applicable to domestic venture capital institutions, while domestic funds face some tax disadvantages due to international treaties.

Like private equity, venture capital has been hit by the global credit slump. Fundraising in the world’s largest venture capital market, North America, has slowed and will likely decline further into 2008, according to the US National Venture Capital Association (NVCA), a trade and lobbying group based in Arlington, Virginia, that represents nearly 500 VC firms.

US-based funds raised US$9.1 billion globally in the second quarter of 2008, a rise of just 3% in dollar value, while the number of funds raised decreased 14%. However, the same American venture capitalists invested US$238 million in India across 17 deals during the second quarter, a 120% rise over the same period in 2007, according to the Dow Jones VentureSource Quarterly India Venture Capital Report.

“We have seen deal activity in India hold steady for three consecutive quarters but this most recent quarter posted the second-highest investment total on record,” says Jessica Canning, director of global research for Dow Jones VentureSource in New York. India may account for only 2.5% of venture capital investment worldwide but, says Mark Hessen, president of the NVCA, India and China remain the “key focus markets” for US venture capitalists.

The biggest contributor to the year’s second-quarter jump was the Rs2.76 billion (US$65 million) investment by Warburg Pincus in Mumbai-based Laqshya Media, a billboard advertising company. Amarchand Mangaldas advised Laqshya on the Indian legal issues.

Just as private equity giants like Warburg are taking on the roles of venture capital investors and funding startups, venture capital firms are funding later-stage Indian companies. “The lines between venture capital and private equity are blurring in India,” says Navin Chaddha, managing director of the Silicon Valley based Mayfield Fund, which has US$2.6 billion under management in the US, China and India.

Other countries are also hopping on the Indian bandwagon. In January, Britain’s prime minister, Gordon Brown, announced that the United Kingdom would set up a network for providing venture capital to Indian entrepreneurs. Separately, CDC Group, a British fund of funds, plans to launch its first Indian venture capital fund with a focus on information technology, healthcare and pharmaceuticals. London-based Pi Capital is also looking to enter the Indian markets.

Venture capital, however, remains hampered by obstacles similar to those facing private equity investors. “The equity market is not well-developed for early-stage investment,” notes Swati Deva, a lecturer in law at Hong Kong Polytechnic University and a former associate at FoxMandal Little in New Delhi. Rafiq Dossani, a senior research scholar at Stanford University who studies the Indian economy, adds that regulatory costs in India keep away investors who have less than US$2 million to invest.

Streamlined regulations fuel growth

Although India remains a small piece of the global private equity jigsaw, it is significant that the major players are turning their attention to the country. For one thing, India is still expected to post 8% economic growth in 2008. Secondly, private equity fills an investment gap that traditional lenders can’t provide for. Thirdly, because private equity came to the forefront only in the late 1990s, local regulations are relatively modern and streamlined.

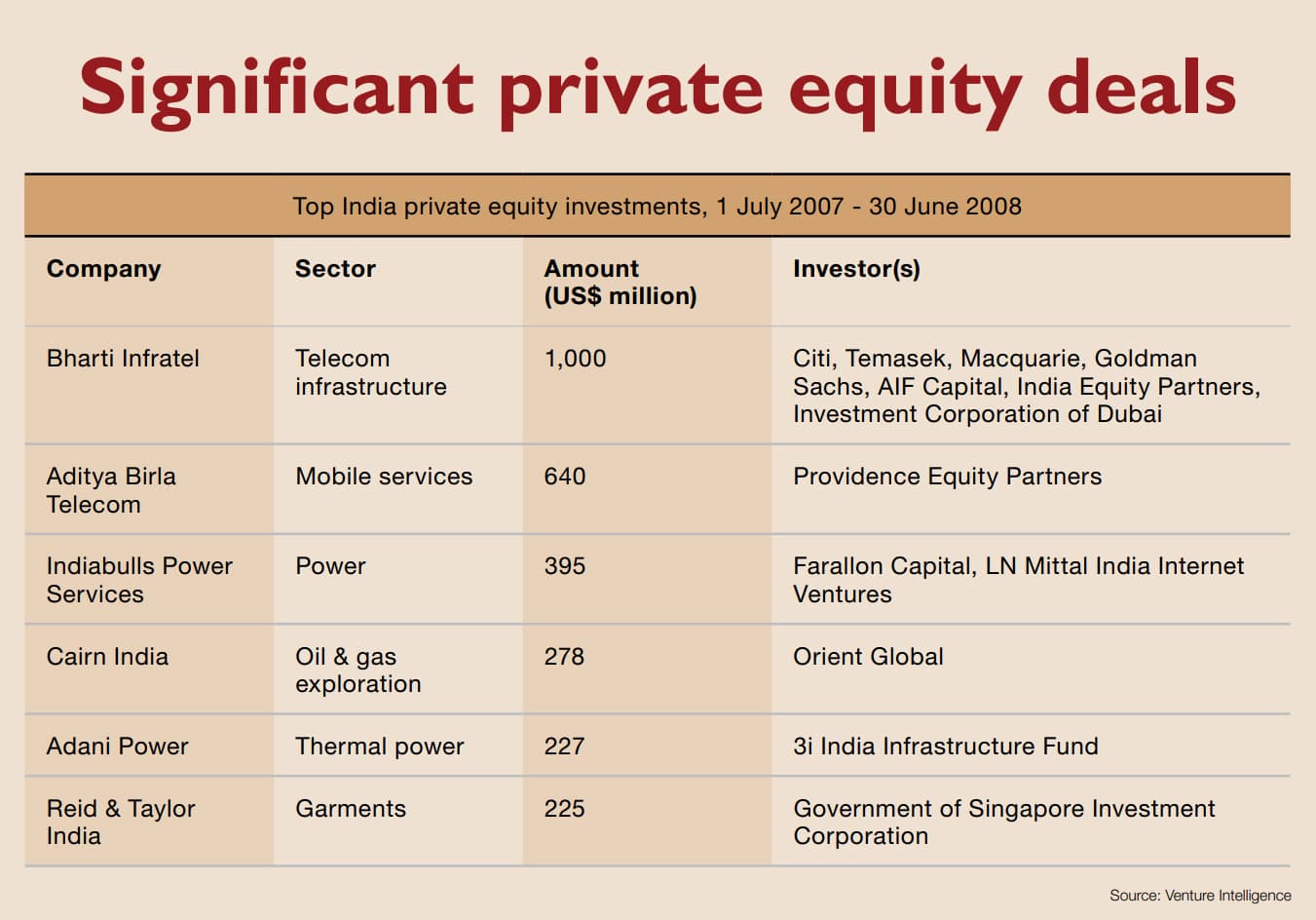

“Private equity as a financing option as we understand it today finds its emergence in the late 1990s, which saw a significant setback with the dot-com bust in the early part of the millennium but made a dramatic comeback with the boom witnessed over the past three years,” says Vandana Shroff, a partner with Amarchand Mangaldas in Mumbai. Shroff’s firm, along with Debevoise & Plimpton, advised Aditya Birla Telecom on Indian law in the US$640 million investment in the company by Providence Equity Partners, the largest reported investment in the second quarter. Amarchand Mangaldas, along with Davis Polk & Wardwell, also represented Cairn India in a US$278 million investment by Orient Global.

International private equity funds can invest in almost all Indian sectors opened up for foreign investment up to the permissible limits for other foreign investors. Furthermore, investors say that India has become an easier investment location than China since Beijing enacted its Provisions for the Acquisition of Domestic Enterprises by Foreign Investors in 2006.

“On the whole, India has been an attractive private equity investment destination on account of various tax incentives also being extended to various sectors and activities,” says Vineet Aneja, a partner at FoxMandal Little in Delhi. The firm has been an active participant in major private equity deals. As well as the Alchemy deal, the firm also advised Gresham Private Equity on its £110 million (US$203 million) investment in BETTS India and the management buyout of BETTS Global and Soma Enterprises on a US$100 million private equity investment by 3i Private Equity Fund.

Private equity funds are also banking on India’s “infrastructure deficit”. According to India’s prime minister, Manmohan Singh, the country needs at least US$350 billion in infrastructure investment during the 11th Five-Year Plan (2007-2012), and needs to raise infrastructure investment from 3.5% of GDP in 2007 to 8% of GDP by 2012.

Infrastructure projects can offer the kind of predictable and sustainable cash flows that private equity investors demand. A recent government report, the National Maritime Development Programme, envisages at least US$2 billion in private-equity investments in shipping, ports and maritime services over the next five years.

Indeed, the five largest private equity deals struck in the past 12 months have been in key infrastructure sectors such as power and telecommunications. (See table: Significant private equity deals on page 17.)

Mallesons Stephen Jaques recently advised Macquarie Bank on a proposed Indian infrastructure fund, while Delhi-based Seth Dua & Associates advised on a US$30 million investment by Axis Private Equity in Harish Chandra (India), a company engaged in the execution of government contracts for civil infrastructure works.

In other large deals, Zia Mody led an AZB & Partners team advising Singapore’s Temasek Holdings, which accounted for US$500 million of a US$1 billion investment in Bharti Infratel along with AIF Capital, Citigroup, Investment Corporation of Dubai, Goldman Sachs, Macquarie Group, and India Equity Partners. Meanwhile Nishith Desai Associates advised Farallon Capital in its investment (along with LN Mittal India Internet Ventures) of US$395 million in Indiabulls Power Services.

Other major transactions include Cleary Gottlieb Steen & Hamilton advising First Reserve Corporation in its investment in Kenersys, an Indian wind energy company, and representing Fortress Investment Group in its acquisition of a stake in Reliance Telecom Infrastructure. Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer advised Siemens on the sale of its water treatment system subsidiary VA Tech Wabag to Indian private equity group ICICI Venture. M&A experts Martin Brodey and Márta Bodrogi at Vienna-based Dorda Brugger Jordis advised Wabag.

Negative perceptions

The biggest obstacle to private-equity investment in India is the controversial nature of private equity itself. The value of private-equity-owned companies in the US is only 5% of the value of listed companies. (The comparable figure in the European Union is just 3%.) However, in 2007 private-equity firms accounted for nearly a third of all mergers or acquisitions deals.

Furthermore, private equity firms have a poor public image worldwide. They have long been referred to as “vultures” gathering around vulnerable companies. Last year, a British trade union leader, Paul Kenny, dubbed them “amoral asset-strippers after a quick buck”. In 2005, Franz Müntefering, former leader of Germany’s Social Democrat Party, famously referred to private equity firms as an “invasion of locusts”.

Indian leaders have not had as much exposure to private equity strategies as Europeans, but consultants acknowledge there could be major issues. “There are chances that the private equity firm undertakes certain measures such as cost cutting or an employee headcount rationalization which, rather than doing anything good to the firm, ends up harming the very culture of the organization that formed its core values,” acknowledges Bundeep Singh Rangar, chairman of Mumbai-based IndusView Advisors, which advises multinational corporations in India.

India’s arcane foreign-investment rules mean there is no sign yet of the multi-billion-dollar mega-deals that the US has witnessed – such as the February 2007 buyout by KKR and Texas Pacific Group of energy giant TXU Corporation (now Energy Future Holdings Corporation) for US$45 billion, and the takeover by KKR, Bain & Co and Merrill Lynch’s private equity unit of healthcare company HCA for US$33 billion in 2006.

Local opposition

If such mega-deals were attempted in emerging economies, it is possible they may flounder under the weight of regulation or sensitivity to foreign control as the collapse of The Carlyle Group’s planned investment in China’s Xugong Group Construction Machinery after three years of negotiations illustrates. The deal finally soured in July after the Chinese government, which initially opposed the deal, ordered Carlyle to cut back its bid from 85% of the company to a minority stake.

Like China, India has its own political roadblocks. The proposed acquisition by Blackstone of a 26% stake in Ushodaya Enterprises, the publisher of one of South India’s largest newspapers, for US$275 million, fell by the wayside in the wake of opposition from local cultural activists, unions and business rivals. The US private equity group had to settle for a much smaller slice of the Hyderabad media company.

Private-equity funds are also often accused of seeking short-term profits, but, globally, many buyouts have improved the performance of the companies taken over. A recent US study of leveraged buyout deals found that two-thirds of them improved fiscal performance and the companies posted returns of twice the industry average. Private-equity firms are also expected to usher in new models of corporate governance to India.

Rana at Goodwin Procter notes that India has a strong family business culture, which has bred an unwillingness to cede control to private equity investors. Philip Millward, a private equity partner with Walkers in Hong Kong, agrees that there can be conflicts: “One disadvantage is the insistence of private equity funds to take quasimanagement positions within the investee companies which, while potentially adding value, can be perceived by the investee company as an encroachment on its ability to independently control the growth and direction of the business.”

Some lawyers, however, see this culture changing. “The growing trend of Indian businesses moving away from the family-run enterprises to seek capital from outside or including professionals in company management presents significant opportunities for [the] development of private equity,” observes Akil Hirani, managing partner of Majmudar & Co in Mumbai.

“Most private equity funds bring more than just money at the Indian promoters’ disposal,” says Bijesh Thakker, managing partner of Thakker & Thakker in Mumbai. “The fund managers and administrators are able to provide knowledgeable inputs on the sector and guide the Indian promoter at critical junctions.” Thakker’s firm recently advised Morgan Creek Capital on issues relating to the placement of an offshore fund and assisted ePlanet Ventures in structuring a private placement.

Ripe opportunities in diverse sectors

Private equity firms are also staying around longer, thanks to the credit crunch. The downturn is forcing private equity firms to ease up on new deals and concentrate on improving companies already in their portfolios. David Rubenstein, cofounder and managing director of The Carlyle Group, said recently that the average holding period is likely to rise to between four and six years, far above today’s levels.

In February, amid the deepening US downturn, Rubenstein told the annual Wharton Private Equity and Venture Capital Conference in Philadelphia that in order to revive the industry, private equity sponsors would need to scale back the size of deals, reduce leverage and look overseas for opportunities in countries such as India and China.

Meanwhile, Indian investors could use private equity strategies to gain access to untapped markets in developed economies that they can fulfill with cheaper Indian imports. In December 2007, Pune-based Tata Motors acquired Jaguar Cars and Land Rover from Ford Motor, while another Pune industrial giant, Bharat Forge, tied up with a French company in order to make deals with PSA Peugeot Citroën. Now, analysts say Indian private-equity groups aim to take over European car-parts companies so they can acquire relationships with manufacturers.

Attitudes towards private equity in India have also improved in the wake of successful exits – such as the profitable departure by Warburg Pincus from Bharti TeleVentures. (Warburg Pincus paid US$292 million for a 19% stake in Bharti Tele-Ventures and sold 9.35% of a diluted 15% stake for US$768 million in 2005.) However, such successes have also upped the ante in terms of Indian companies setting the terms for investments. Rana says that has led to more minority investments, whether in private companies or private investments in public equity.

In India, private equity investors are drawn to diverse sectors. Venture Intelligence found that telecommunications and power companies are continuing to draw capital, while healthcare and life sciences have gained a higher profile. Baer Capital Partners’ investments range from facilities management to vineyards, art galleries to hospitality. (Norton Rose led advice to Baer Capital Partners on the establishment of the Beacon India Alpha Equity Fund, an open-end Mauritian domiciled investment fund.)

Even the food and beverage industry has lured investment. Erasmic, a fund backed by Google, invested in Bangalore-based fast-food chain Kaati Zone, while London law firm Grundberg Mocatta Rakison acted for India Inflexion Fund on an investment into a leading Indian restaurant group. Kanga & Co, meanwhile, represented Navis Capital Partners in the sale of its stakes in Mars Restaurants and Sky Gourmet to India Hospitality Corporation.

Nowhere has the startling growth of private equity been more visible than in real estate and construction. The sector attracted just US$1 million in 2005, US$820 million in 2006 and US$2.6 billion in 2007. Recently, J Sagar Associates represented The Carlyle Group in its investment in Repco Home Finance, while Khaitan & Co advised Aanya Advisors and Intec Partners in setting up a fund to invest in real estate projects in India. In addition, FoxMandal advised Alpha Real Capital in the formation of a US$35 million real estate fund.

Regulatory restrictions and delays

Most foreign funds invest into India through holding companies set up in Mauritius, Singapore or Cyprus. Such countries have double taxation avoidance agreements with India, which provide capital gains tax benefits and lower withholding taxes. “These holding companies then invest into the Indian investee company in the form of compulsorily convertible preference shares along with equity shares, which may carry disproportionate voting rights,” notes Vishal Gandhi, managing partner of Gandhi & Associates in Mumbai.

The biggest challenge is the restrictions under the Foreign Exchange Management Act, 1999, says Gandhi. “For example, optionally convertible preference shares are treated as debt and the funds raised from their issuance cannot be used for general corporate working purposes. These restrictions lead to a complicated deal and share capital structure, since the funds attempt to achieve their objectives with alternative and mixed instruments.”

One key concern is the delay in getting regulatory approval and there is often a backlog.

“A particular challenge over the years has been regulatory approvals required in the event the investor has made a prior investment in the same field or has a joint venture partner in India in the same field as a proposed new investment,” says William R Kirschner, a partner with White & Case in Washington. “The Indian government has felt compelled to try to protect Indian business from foreign competition, despite the fact that Indian business is at the forefront of many industries now and, in fact, are actively engaged in investment activities of their own outside of India.”

There are still some restrictions for Indian corporate entities in terms of capital markets fundraising, particularly if they wish to make use of offshore financing options. Bharat Banka, CEO of Mumbai-based Aditya Birla Capital Advisors, agrees that the current regulations on bank financing for investments in India are a constraint for larger leveraged deals. “With changes, this area could open up in a big way,” he says.

Kirschner cites several other obstacles, including government-imposed pricing formulas for investments by foreign investors; restrictions on convertible securities and debt investments and the new competition law, “all of the ramifications of which are yet to be articulated by the government”.

Taxation issues also remain onerous, lawyers say. “The global private equity industry has favourable tax laws and structures like limited liability partnerships which are yet to be made available in India,” says Banka. “With changes, the investment flow in private equity could increase as the funds would be able to access domestic capital and the investment management talent from within India.”

One streamlined private equity process is the pre-IPO investment. “Pre-IPO deals typically are straight common equity with relatively few governance rights attached,” says Gerstell at Milbank. “When a company eventually goes in for an IPO, public market investors take significant comfort from the fact that PE investors are already on board and hence would have ensured high levels of corporate governance.”