The Belt and Road initiative dwarfs the Great Wall of China, and pretty much anything else on earth, in its perceived magnitude. In the first of a special series of articles, Andy Gilbert looks at the germination of the initiative and traces its growth so far

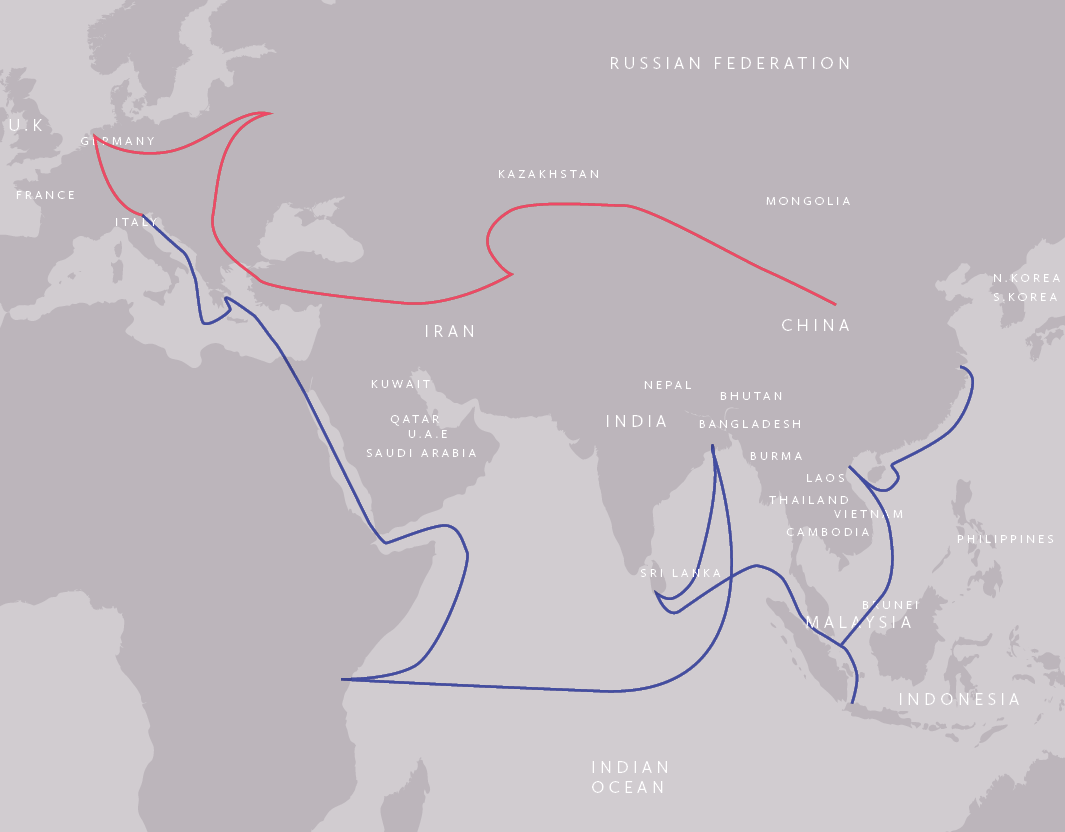

If the whole is greater than the sum of its parts, then the One Belt, One Road (OBOR) initiative is undoubtedly the biggest infrastructure project ever conceived. Six economic corridors running through Asia, Europe and Africa, connecting vibrant economies of East Asia at one end with developed Western Europe at the other. A massive upgrade of the region’s infrastructure: roads, railways, ports, power stations; interconnected via more than 65 countries covering almost two-thirds of the world’s population, one-third of global GDP, and a quarter of all goods and services worldwide. Even Aristotle might have raised an eyebrow.

In other ways, however, it’s perhaps not quite what it seems. Layered beneath the millions of tonnes of concrete lies China’s push to take a bigger role in global affairs, its need to export excess production capacity in areas such as steel manufacturing and infrastructure construction, and so expand its political influence, internationalize the renminbi, and kick-start its economy amid slowing growth in exports and fragile domestic demand.

“OBOR is a concept rather than any detailed plan,” says Ronald Sum, a Hong Kong-based partner at Troutman Sanders. “On the commercial side, the OBOR initiative is predominantly to promote trade and investments among various OBOR countries. On the non-commercial side, it is the ultimate integration of different systems – economy or otherwise – within the OBOR countries.”

It’s certainly not without controversy, or scepticism at the very least. Some China watchers have called the initiative financially unsound and unsustainable, with a price tag in the region of US$8 trillion. Certain projects, almost entirely financed by Beijing, have even been likened to Chinese economic aid rather than bilateral investments, with all the resulting influence cynics would point out that brings.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

Riding the silk road E-highway

The Belt and Road may be the land-based infrastructure of the Silk Road Economic Belt and the ports and shipping routes of the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, but a third avenue – the Silk Road e-highway – is likely to become perhaps even more important, as e-commerce increasingly facilitates most of the trade along its routes.

At the forefront of this is China’s Alibaba Group, the world’s biggest e-commerce company, whose B2B and B2C platforms are aiming not only to facilitate trade but also to educate the newest players who are likely to take advantage of the Belt and Road initiative.

“Our in-house lawyers play a significant role in this regard,” says Cindy Hui, senior legal counsel at Alibaba Group. “For our lawyers it’s about coming up with the structures, with the direction, understanding the limitations of each country in terms of international trade, research on customs laws, tax laws, consumer protection, trade barriers, anti-trust laws, anti-competitive laws.”

Overcoming the language barriers between markets and understanding local customs and methods is also key. “In terms of what the legal challenges are, when we try to break into local markets there are obviously existing local players,” says Hui. “So how do we collaborate with them or understand the market and make a proportion of market share for our businesses? This is a legal challenge because we need to understand, without being a local, what the restrictions are, such as tax restrictions and customs restrictions, so we can make our businesses successful and scalable.”