With a relentless demeanour and the stamina to remain in the game for longer than an Indian test opener, Lalit Bhasin discusses the finer nuances of life, law and legacy with Gautam Kagalwala

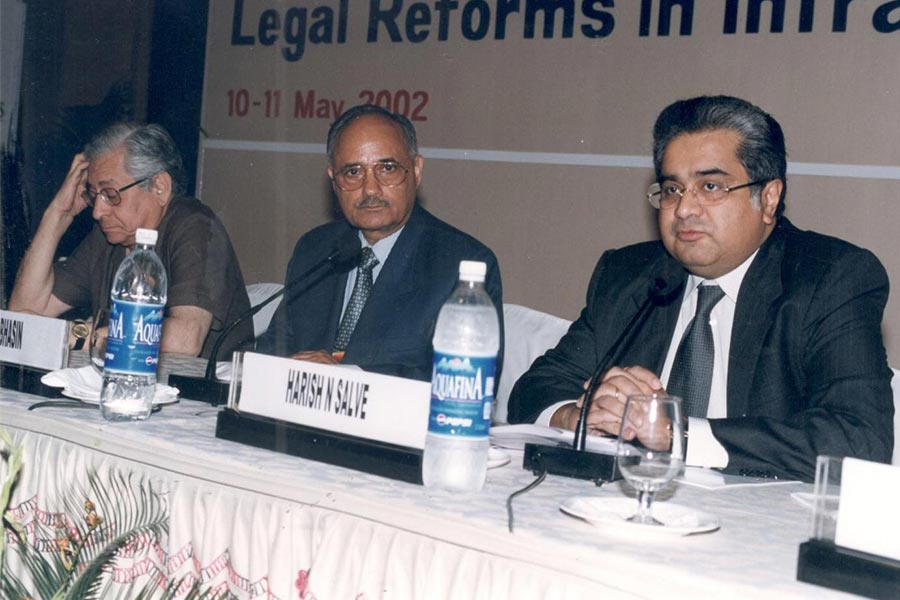

He is one of the best-known names in India’s corporate legal world. With a practice that began back in 1962, Lalit Bhasin recently reached two more career milestones – completing 60 years in the legal profession; and being elected as national president of yet another powerful influential group, the Indo-American Chamber of Commerce (IACC).

The latter is one of a string of executive appointments over the years, which in many ways goes to the fibre of Lalit Bhasin – lawyer, steadfast legal campaigner, champion for those with the legal will but not the way, past defender of the status quo and present fomenter of change.

To understand the man more completely, it helps to view the past. A fourth-generation lawyer, Bhasin recounts proudly how his family served the nation by working as freedom fighters against the British Raj.

“My father was a great lawyer, always fighting for the rebels, even after independence, and he was one of the most distinguished lawyers,” he says, adding that this left him with a large legacy to make justice an integral part of the public experience.

The partition drew a bloody line between the two countries, and gave rise to waves of population movement in both directions.” Bhasin talks about his great grandfather hailing from Rawalpindi. “My great grandfather was also a lawyer in Rawalpindi, which of course is now in Pakistan – he was a freedom fighter, a great Congress leader of Punjab.”

From humble beginnings all those decades ago to the present, and there is a distinct difference between the humble shingle of Bhasin & Co when compared with larger law firms like Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co, Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas, AZB and Khaitan & Co.

Unlike the country’s largest law firms, some of which have grown to almost 1,000 lawyers in strength, Bhasin’s focus was not on the size of his legal practice. He was looking elsewhere.

“At that time, of course, we didn’t have law firms – except three or four firms in New Delhi and about five or six in Mumbai and Kolkata, and Madras,” he recalls. “But essentially, it was litigation lawyers, you see, who were there. So, right from the beginning, my idea was to do something for the profession, particularly the young lawyers, the disadvantaged lawyers, the disabled and indigent lawyers.”

When he was 33, Bhasin became the youngest person to be elected chairman of the Bar Council of Delhi. His goal was to enable lawyers in the country to come up to the level of their international counterparts, a vision that engendered his vehement opposition in the 1990S to the entry of foreign law firms into India.

“I wanted the Indian law firms to grow, so that they could meet the challenge, which will be there from the foreign law firms.”

Time to change

Bhasin’s fervent and well documented views on keeping out foreign lawyers have softened, he says, with the development of the capabilities and growth of Indian firms across the country. “These law firms are second to none as compared to foreign law firms, both in terms of quality and speed, that is, expeditious disposal of opinions, or matters or transactions, and also in terms of resources.”

In 2014, Bhasin suggested to the Ministry of Commerce that foreign law firms could come to India in a staggered manner, as was contrived in Singapore. “Now we are in a position to face a good challenge and good competition from our counterparts across the globe,” he says.

“So, from 2014 until now, we have been open about foreign lawyers coming to India, and I’m speaking on behalf of not only the Society of Indian Law Firms, but also on behalf of the Bar Association of India, as the immediate past president of that association.”

Leveraging for foreigners

Against the backdrop of ongoing negotiations for an Indo–UK trade deal, and such a deal’s implications for opening up India’s legal sector, Bhasin says he has been meeting senior figures in the UK government in this regard.

He believes that to bring about change, it is necessary to overcome judicial precedent and amend the Advocates Act. But the initiative has to come from the government of India and the parliament of India because, in keeping with a Supreme Court judgment delivered in 2018, only Indian citizens can practise law in India. And that means any type of law whether it be Indian law, foreign law, transactional law or litigation.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.