In today’s world of finance, it is common to hear reference to subordinated debt, particularly in the context of capital-raisings by banks when they issue subordinated bonds.

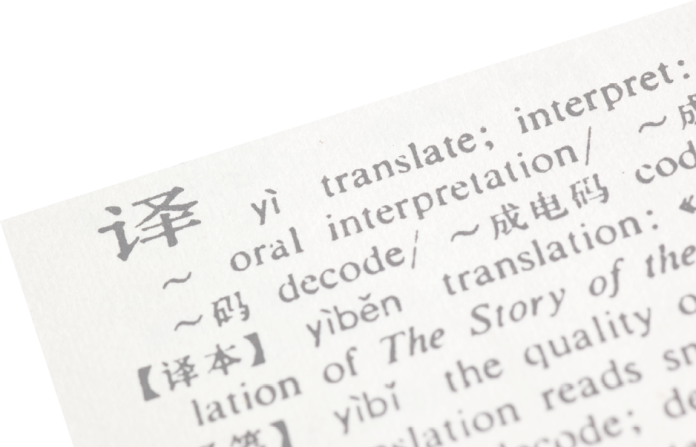

The English verb “to subordinate” means to treat something as of lesser importance than something else. The English adjective “subordinate” means to be lower in rank or position, as in the phrase “subordinate personnel” or “subordinate legislation”. The English word is derived from two Latin words: “sub”, meaning “below”, and “ordinare”, meaning “to rank”. When put together, the two words mean “to give something a lower rank”.

Thus, subordinated debt is debt that has a lower rank (or priority) than other debt. The equivalent word in Chinese (次级债务) is much easier to understand, as it literally means “second-ranked debt”.

This article first explores the concept of debt subordination and then outlines its legal treatment in three common law jurisdictions – England, Australia and Hong Kong – and in mainland China.

The concept

The concept of debt subordination is relatively simple. It describes the situation where a creditor agrees that its debt – i.e. its claim against a debtor for payment of a debt – will rank behind another debt (or other debts). In other words, the creditor agrees that its debt will not be paid until another debt (or other debts) have been paid. Debt subordination may occur by contract between creditors after the relevant debts have been created. Alternatively, it may be a structural part of the debt itself.

For example, when banks raise capital by issuing subordinated bonds, the terms of the bonds themselves provide that the debt will be subordinated to debts owed to all other creditors. In such circumstances, the arrangement is not created by a contract between the bondholders and the other creditors – this would be impractical as the number of the creditors would be too great.

The focus of this article is on the former situation; namely, where one creditor (the junior creditor) enters into a contract with another creditor (the senior creditor) under which the junior creditor agrees that its debt claim against a debtor will be subordinated to the debts of the senior creditor. This may arise in a range of circumstances. For example, a parent company that has provided a shareholder’s loan to a subsidiary may agree to subordinate its debt in favour of a bank that is going to provide a loan to the subsidiary. Otherwise, there would be a risk that the subsidiary would use the bank loan to repay the debt owing to the shareholder. Alternatively, a lender may agree to provide a loan on a subordinated basis in return for receiving a higher rate of interest from the debtor company.

In such circumstances, a typical debt subordination agreement that is governed by English law provides that before the debt of the senior creditor is paid:

- The junior creditor will not demand repayment from the debtor or exercise any rights of set-off against the debtor (for a discussion of set-off, see China Business Law Journal volume 6 issue 4: Set-off);

- The junior creditor will not take any enforcement action to recover its debt from the debtor, except with the consent of the senior creditor;

- If the junior creditor receives any amounts paid by the debtor in respect of the subordinated debt, the junior creditor will hold such amounts on trust for the senior creditor; and

- If the debtor enters bankruptcy proceedings, the junior creditor will prove its debt if requested by the senior creditor (for a discussion about bankruptcy, see China Business Law Journal volume 4 issue 10: Bankrupt or insolvent?).

The best way to illustrate how debt subordination works is to give an example. Let’s say that two creditors of a company enter into a subordination agreement. Each of the junior creditor and the senior creditor is owed $100 by the company. Let’s also say that the company becomes insolvent (i.e. the value of its assets is less than its liabilities) and its assets are valued at only $150. In addition to the debts of $200 that it owes to the junior and senior creditors, the company owes a debt of $100 to a third party. Thus, the company has assets of $150 and liabilities of $300. We are assuming that all creditors are unsecured; namely, none of the creditors holds any security over the assets of the company.

In the absence of the subordination arrangement, the company (or its liquidator) will only be able to pay $50 to each of the creditors. In other words, each creditor will only recover 50% of its debt. If the junior creditor does not prove its debt (i.e. it does not file a claim for its debt in the bankruptcy proceedings), the senior creditor and the third party will each receive $75. However, if the junior creditor proves its debt and agrees to pay the amount that it receives from the liquidator to the senior creditor, the senior creditor will recover the full amount of its debt (i.e. $100) and the third party will receive $50.

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.

你需要登录去解锁本文内容。欢迎注册账号。如果想阅读月刊所有文章,欢迎成为我们的订阅会员成为我们的订阅会员。

Andrew Godwin

A former partner of Linklaters Shanghai, Andrew Godwin teaches law at Melbourne Law School in Australia, where he is an associate director of its Asian Law Centre. Andrew’s new book is a compilation of China Business Law Journal‘s popular Lexicon series, entitled China Lexicon: Defining and translating legal terms. The book is published by Vantage Asia and available at law.asia