In the second of a three-part examination of China’s Belt and Road initiative, Asia Business Law Journal looks at concrete examples of how law firms are bringing the scheme’s dreams to fruition through large-scale infrastructure and project finance deals. George W. Russell reports

At first glance, web surfers in Kazakhstan would appear to have little in common with bookworms in Tanzania. Yet both are already beneficiaries of China’s ambitious Belt and Road initiative, which seeks to link 60-plus countries through about US$900 billion in spending, mostly on infrastructure.

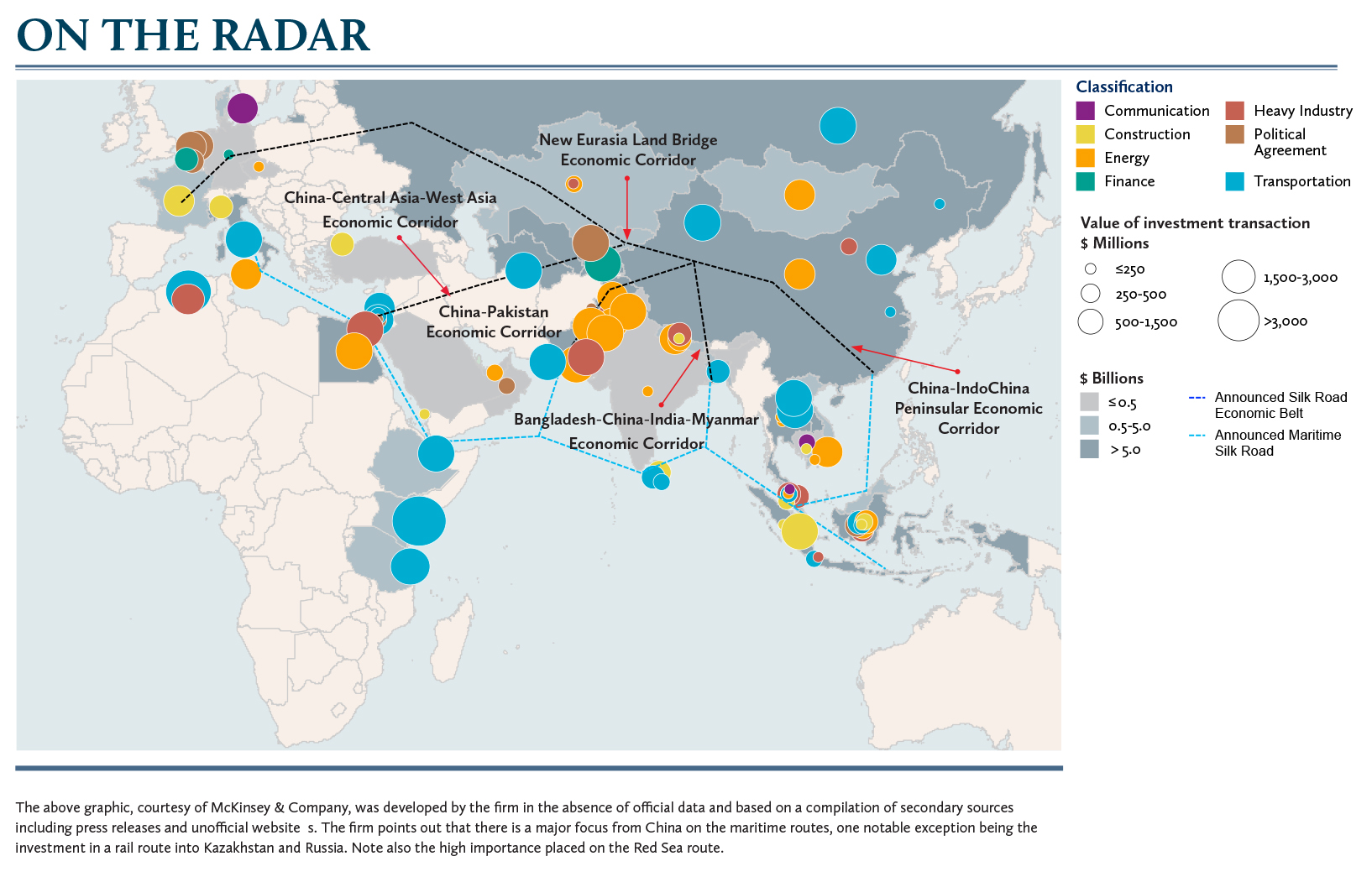

Just four years since Chinese President Xi Jinping announced the Belt and Road initiative – comprising a land route, the Silk Road Economic Belt, and a sea link, the 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road – headlines have trumpeted a seemingly unstoppable wave of project announcements.

The initiative’s core projects include a US$50-billion-plus overland corridor, from Xinjiang in China to Gwadar in Pakistan. Other big-ticket items include a US$4 billion high-speed rail line from Kunming to Singapore and a US$1-billion-plus port development near Colombo, Sri Lanka.

To fund such mega-projects, Beijing has created a raft of new lending vehicles, such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), supported by 57 countries, which boasts more than US$100 billion of initial capital to be spent largely, though not wholly, on Belt and Road projects.

In addition, the US$40 billion Silk Road Fund, launched in 2014 by China Investment Corporation, China Development Bank (CDB), Export-Import Bank of China and the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, is dedicated to Belt and Road investment. In 2015, three banks – CDB, Export-Import Bank of China and the Agricultural Bank of China – were given a total of US$82 billion in central government funds to lend for related projects.

These huge sums – and the Belt and Road’s global reach – have inspired awe, with comparisons to the US Marshall Plan that rebuilt Europe after World War II. “The Belt and Road initiative has become a central strategy for the Chinese government to boost domestic development and cross-continental collaboration,” says Hu Yifan, chief China economist at UBS, a major bank.

For law firms, Belt and Road is a shot in the arm for project finance. “[AIIB] is the biggest shake-up of the multilateral funding landscape in decades,” says Fang Jian, a partner at Linklaters in Shanghai. “It will add considerable depth and complexity.”

The scheme has also attracted scepticism. David Brewster, an expert on strategy at the Australian National University’s National Security College – and a former partner with Gilbert + Tobin in Sydney – notes that the initiative “requires co-operation among many countries that are politically unstable, corrupt or experience high levels of civil conflict”.

Law firms are aware of the choppy seas ahead. “It is inevitable that large numbers of Belt and Road initiative projects may proceed on the premise of legal uncertainty and with a degree of scope for failure,” says Neil Cuthbert, senior partner for the Middle East at Dentons in Dubai.

Yet several smaller projects that have been commissioned along the routes are already changing lives. For example, financing from the Silk Road Fund will pay for both the laying of fibre-optic cables that will enable rural villages in Kazakhstan to access the internet, and the publication of a range of Swahili-language versions of Chinese business and text books to be sold in Tanzania.

Hype and happenings

Corporate China is energized about what Belt and Road can do for the economy. “The initiative should be able to increase the influence of China in countries along the route and attract more customers to the China market,” says Stephen Wong, chief financial officer of TTL Holdings in Shanghai, which operates high schools in China that follow a US curriculum.

Beijing has already put in place incentives to attract companies to Belt and Road locations. “We see the benefits of tax incentives, easier financing and faster approval of outbound investment in Belt and Road-preferred sectors,” says Steven Li, vice president in the international division of Sanpower Group, a diversified conglomerate based in Nanjing.

There are hazy ideas about what constitutes a Belt and Road project: the Chinese-built port at Gwadar, in Balochistan province in Pakistan, was on the drawing board long before Belt and Road was announced. Some of the flagship projects, such as the rail link between China and Europe, have doubtful revenue projections. Recent trains have been mostly for show, hauling low-value goods like socks.

Whether or not some Belt and Road numbers are fudged, the optimism underpinning the overall initiative is real. For example, Hong Kong’s Mass Transit Railway Corporation announced on 18 May that it would team up with partners in China to explore Belt and Road-related opportunities. Its shares almost immediately rose 1.3%.

The big lure for investors is the large-scale infrastructure. Paul Starr, a partner at King & Wood Mallesons in Hong Kong, works on the deals that help build the physical backbone of the Belt and Road. “I always talk about holding the hands of our clients,” he says. “That means travelling out with them to their future or actual Belt and Road projects – to help them negotiate their tenders, assess risk, prepare for and hopefully avoid claims,” he says. “We have already seen ourselves travelling out to India and Pakistan in that role.”

Pakistan is a major hub for early Belt and Road projects: Fang and colleague Ji Xiaohui of Linklaters advise on the Thar Engro Coal independent power producer (IPP) project in Sindh. The firm’s related deals include the Yamal liquefied natural gas project in Russia and another IPP in Indonesia.

Belt and Road has energized the world’s infrastructure capitals. Cuthbert at Dentons says his firm’s Dubai office is working on IPPs as well as power purchase agreement projects and private-public-partnership (PPP) matters. From London, Fladgate is advising a Central Asian country on the design, construction, finance and operation of a hydroelectric power plant as well as working on financing structures and risk allocations.

“With the exception of these early projects,” notes construction, infrastructure and projects partner Alan Woolston, of Fladgate in London, “to date our involvement has primarily been in an advisory capacity to introduce the United Kingdom experience of major projects procurement.”

You must be a

subscribersubscribersubscribersubscriber

to read this content, please

subscribesubscribesubscribesubscribe

today.

For group subscribers, please click here to access.

Interested in group subscription? Please contact us.